Crowdfunding Urbanism

Crowdfunding is known as an effective way to support innovative ideas and intentions. Especially when it comes to independent music publishing and event management, as well as for product design, crafts and small scale projects crowdfunding is established as a working tool. To use crowdfunding in the urban planning procedure is by now a mainly untested, but promising field. It arises out of a desire to make the process of urban development more legible. The call for more transparency in decision-making and self-governance demand a new instrument for the public’s participation.

For aspiring entrepreneurs, Indiegogo’s founder Danae Ringelmann’s advice is simple – “Don’t wait for perfect. Get started as early as you can, and don’t try to boil the entire ocean at once. Many people get paralysis from analysis, where they design their perfect business plan, or their perfect non-profit, or their perfect album, and when this analysis keeps you from taking action, that’s no good.”[1]

The following article will answer some important questions about public property, financial system operations, potentials and problematic and will give a possible vision to use crowdfunding for urban planning in a realistic and successful way.

Contents

- 1 Basic Facts

- 2 Crowdfunding as an appropriate tool for urban planning

- 2.1 Potential of crowdfunding in the urban planning process

- 2.2 Risks of crowdfunding in the urban planning process

- 3 Legal situation

- 4 Crowdsourcing in Public Spaces

- 5 Prospect

- 6 Literature

- 7 References

Basic Facts

"Crowdfunding is the practice of funding a project or venture by raising many small amounts of money from a large number of people, typically via the Internet.”[2]

In accordance with the perspective of Jeffrey Hou, the author of the book 'Now Urbanism: The Future City is Here', Crowdfunding Urbanism means:

"a new model for city making with the tactiacal temporary intervention. 'User-generated urbanism' ia an attempt to synthesize the strategic and tactical dimensions of city planning, of centralized hierarchies and distributed peer-to-peer networks. Using a people-centered approach, strategic entities – rather than creating a city for urban residents to consume – could offer up a content platform that urban residents can shape according to their own desires, thus giving urban residents the freedom to build the city they inhabit." [3]

Terms and Definitions

CROWD

means a large number of persons gathered together, a throng; a group of people united by a common characteristic, as age, interest, or vocations; a group of people attending a public function; an audience: The play drew a small but appreciative crowd; a large number of things positioned or considered together.[4]

FUND

is a saved, collected or provided amount of money for a particular purpose; needed or available money to spend on something[5]

PUBLIC SPACE

According to our research the definition of a public space is very flexible. Therefore we have listed a number of definitions that describe the meaning of shared space in our context accordingly:

„A public space may be a gathering spot or part of a neighborhood, downtown, special district, waterfront or other area within the public realm that helps promote social interaction and a sense of community. Possible examples may include such spaces as plazas, town squares, parks, marketplaces, public commons and malls, public greens, piers, special areas within convention centers or grounds, sites within public buildings, lobbies, concourses, or public spaces within private buildings.“ [6]

"A public space or a public place is a place where anyone has a right to be without being excluded because of economic or social conditions, although this may not always be the case in practice..." [7]

"Public space is the stage upon which the drama of communal life unfolds. The streets, squares and parks of a city give form to the ebb and flow of human ex- change ... In all communal life there is a dynamic balance between public and pri- vate activities" [8]

NIMBY

"A person who objects to something considered undesirable, such as a halfway house or industrial plant, being established in his or her neighborhood while being happy for it to be set up elsewhere (not in my back yard)."[9]

YIMBY

"YIMBY is an acronym for Yes In My Back Yard in contrast and opposition to the NIMBY phenomenon. Some of the groups encourage the installation of clean energy sources, such as wind turbines, despite the opposition these generally face from NIMBY groups." [10]

IOBY

"Ioby is a crowd-resourcing platform for citizen-led neighbor-funded projects. Our name is derived from the opposite of NIMBY. Our mission is to strengthen neighborhoods by supporting the leaders in them who want to make positive change, engaging their neighbors, one block at a time."[11]

Conditions

Nowadays almost everyone around the world knows the concept of Crowdfunding, how it works and what it is used for. In the small scale of material things the problems are reduced and can be easily overviewed. If we take a look on the bigger scale, we have to handle with important legal questions and government rules. Although Crowdfunding is difficult to insert in public space, there are a lot of platforms, which see the potential and realise Urban Crowdfunding projects. On this occasion the important questions are: What is the process of financing a new place or a new building, situated on a public space? To whom does this piece of country belong? Who may join in? Who makes the final decision?

Urban Crowdfunding helps to finance projects in the public space, these include activities like embellishing or appreciating urban spaces, building communities and facilities, improving living quality, encouraging connections, pushing forward self motivation, strengthening creativity... Most popular examples for worldwide Crowdfunding projects in urban areas: Imake Rotterdam-Bridge Luchtsingel, New York +Pool, Robocop Statue Detroit, Low line New York, Kulturrisauna, Renew Newcastle,...

Crowd

Via online Platforms, like Spacehive, Citizinvestor, Iobyand, Brickstarter, Neighborland and Co. users can present and describe their ideas of a project. The project conversion implicates high costs. To reach the whole amount for the project, people can help in form of pledging via Crowdfunding Platforms in urban space. If the total investment sum is reached, the project can be realised. Short: Massfinancial system via Online Platforms to change public space.

Most of the funders are relatives or friends, who want to support the dream of the designer to come true. Other funders that support projects get the opportunity to help creating civic spaces more lively by contributing whatever they like. Some people donate projects because it will make their area a nicer place to live in. Some are doing it because it will support the local economy or their business. Others help just because they think the idea is brilliant and want to encourage innovation and creativity in their civic spaces. Supporting a project is more than just pledging funds. It’s a way of voting for the kind of community you want to live in.

In most cases, the majority of funding initially comes from the supporters and friends of each project. If they like it, they’ll spread the word to their friends and networks, and so on. Press, blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and Spacehive itself are big sources of pledges as well. We also have a number of match-funding schemes designed to make it even easier for certain types of project to hit their target.

Participants

Projects can be created by local people, architects, artists, companies, councils, community organisations, and groups of friends,… shortly - by EVERYONE with a great idea. They can be modest or ambitious. Every project is unique and is something that helps to improve the fabric of communities. The only condition is that you must be at least 18 years old. At the age of 18 you are of full age and punished for your own actions and faults.

Charges

Online Platforms just offer available space for ideas and concepts – this service is free of charge. With the realisation of a project, transaction costs occur. Online Platforms charge an administration fee if, and only if, a project successfully hits its funding goal. Usually the fee is about 5% of the total of your item costs. All fees are clearly displayed within the costs for each project. Transaction costs for instance with PayPal deduct fees ranging from 1.4% - 3.4% of the whole amount + 20p per pledge - only if the project hits its funding goal. GoCardless is the second famous online direct debit payments system. The fee for a GoCardless pledge is 0.5% of the pledge.

Online Platforms do not promise to realize the project – they are just a stepping stone for finding potential financiers. It’s the legal responsibility of the Project Delivery Manager to complete his project. Everyone can see who they are by looking at the grey box on each project page. Platforms are not involved in the development or delivery of the projects themselves. They do not guarantee projects but, to help reduce risk, all projects are verified prior to fundraising to establish their viability. The verification process is carried out by experts in civic projects - like Locality and ATCM.

Crowdfunding as an appropriate tool for urban planning

On September 17, 2011, a few hundred demonstrators gathered in lower Manhattan and prepared to occupy Wall Street, the symbolic heart and center of the US financial system. With the slogan: "We are the 99 percent!” the activists occupied a nearby privately owned public space called Zuccotti Park to set up a camp. [12]

These occupations followed a wave of protest around the world (like protests in Spain and Greece against austerity), but were mainly inspired by several movements in the Arabic region, like the Iranian Green Movement in 2009 and the Arab Spring that spread from Tunisia in 2010 to Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, Syria, and elsewhere in 2011. [13]

In general, the occupations of 2011 did not have the same goals. Those of the Arab Spring sought to bring down authoritarian governments; those in Europe protested austerity; Occupy Wall Street (in New York and in its offshoots around the United States) was directed at the financial system and economic inequality. But there were important similarities beyond the similarity of tactic. In each country young people, facing economic, financial and cultural crisis, used social networking media to organize the occupation of Public Space. The occupations are nonhierarchical structured and promoted an egalitarian, non-alienated form of interaction.

As an element of political protest, the occupation underlines the importance of space for social movements. The contemporary analysis of the social significance of space begins with Henri Lefebvre (1991), who argued that space must be understood as more than a neutral container of activity. Space is actively produced, not only in its physical disposition but its social meaning, by the activities that go on in it, or that go on in some spaces but not others. [14]

All social movements are organized in space, but some of them are mainly about space itself.

An occupation, Peter Marcuse argued, "also has a second function: it is an opportunity to try out different forms of self-governance, the management of a space and, particularly if the physical occupation is overnight and continuous, of living together"

As Peter Marcuse explains, "When space is occupied by the movement, it gives a physical presence, a locational identity, a place that can be identified with the movement that visitors can come to, and where adherents can meet". According to David Graeber, an early organizer of OWS, "the great advantage of Zuccotti Park was that it was a place where anyone interested in what we were doing knew they could always come to find us, to learn about upcoming actions or just talk politics" [15]

In this sense, Occupy movement can be understood as political (re-)conquest of public space.

Potential of crowdfunding in the urban planning process

In a direct consequence of the global occupy movement, the value of public space gain more importance in people’s minds. A call is made for a necessary demand to renegotiate the ordinary borders of public. While occupying alleged open spaces, the symbolic space, as well as the actual space is reinterpreted by the community. Common social and political values are questioned, in order to expand the potential of self-governing in urban space.

A shared space belongs to the public and makes participants to individuals with equal political and legal footing in the process of using and defining the open space. In this sense public property can be understood as political process, with the objective to ensure an expanded participation and a democratic self-determination.

Inappropriately the current policy and local bureaucracy are contrary to a preferable participating process in urban planning.

Due to the increasing of privatization and commercialization of public property, also the need for liberation is growing. The regeneration of the strength of potent ideas is effectively mainstreamed by new impulses in urban design and the (re-)discovery of common space by the crowd. The city itself must not remain unimpeachable. The urban design, the urban meaning and the urban use is open in its definition.

Virtual space connects

To achieve the common demand of recovering public spaces an appropriate form of organization, a space, a defined category and a subject is required.

For that matter the virtual space is considered as the important key to more democracy. The internet can be used as common source, which enables a free exchange of ideas and an open participation.

The virtually network has become the dominant cultural capital. A joint study by BVDW, IAB Austria and IAB Switzerland for digital user behavior shows that more than 90% (53 million habitants) German-speaking area uses the internet at least once per day in an average of 3 hours in 2014. The study applies to Germany (92%), Austria (92%) and Switzerland (88%) and records targets between 16 and 69 years. [16]

According to this fact, the internet seems to be a perfect tool to reach a big crowd, as well as to coordinate the projects itself. It demonstrates the missing link between individuals, communities and institutions. A representative platform in a highly connected world can be used to articulate and to communicate between the city’s diverse stakeholders.

The advantage of a space which everybody can enter at any time lays in the fact that the participation of citizens, local business and government are on a higher level. The virtual space occurs as a starting point of action. Due to more possibilities for participation it is a more democratic instrument in the decision-making process than the analogue space with its practical realities of debating and governing.

Crowdfunding as democratic instrument

Crowdfunding is able to establish a new balance between the traditional asymmetry of control by politicians, authorities and experts in contrast to public opinion. It puts debates in the center of the city acting and opens a forum to involve everybody. The traditional decision-making process gets a refresh, with the result that the power is shifted to the audience while citizens are placed first.

The process of crowdfunding allows the participation of the crowd in the very first phase, either due to launching an idea (besides long-term competitions) or due to control the selection of already launched projects. The involvement of the public for a creative project creates a democratic quality criterion, which is outside the influence of the state.

The authors of ‘Acting in an Uncertain World’ argue that political institutions must be expanded and improved to manage these controversies, to transform them into productive conversations and to bring about “technical democracy.” [17]

Michel Callon describes the theoretical concept of a “hybrid forum”, in which experts, non-experts, ordinary citizens and politicians come together for dialog. Callon reveals the limits of traditional delegative democracies, in which decisions are made by professionals and politicians. He argues that the division between professionals and lay persons is simply obsolete. [18]

The method of crowdfunding could implicate such a new kind of dialogic democracy, which enables individuals to reach decisions despite a lack of special knowledge. The intention could be to destabilize the position of experts in master planning and in design processes.

Rodrigo Araya, a pioneer in developing and coordinating citizen participation strategies, from Tironi Asociados in Chile describes in an interview that suddenly they had a reason to put Callons theory into practice. “The results have been extraordinary, with most of the city of Constitución engaged in an intense, constructive public debate, effectively shaping the plan in real-time. Araya’s ‘social team’ led the process, with experts and others shaping and reshaping their proposals in response to the debates.” [19]

It is a proof for cooperative decision-making and collaborative consent. Crowdfunding can offer this by turning all participants into independent equal individuals.

Crowdfunding promotes participation

The prospect of a democratic decision will raise the participation. Through participation new concepts of public space are rising.

Dan Hill, co-author of the 21st century social service prototype ‘Brickstarter’, describes: “Participation is often no more than a sop in urban planning and city politics generally. It’s a token gesture that is partly responsible for generating NIMBY responses, manifesting itself in the wrong kind of engagements (surveys, focus groups, votes) at the wrong times (at the beginning of projects, often pre-proposal, before it’s possible to have constructive discussion, or at the end, when all the decisions have already been made.) Tironi have flipped such projects on their head, organising the entire thing around participation. Although the work is in process—as it always is with cities, it has to be said—the results so far appear to be extraordinary.” [20]

Through crowdfunding platforms citizens get more often in touch with the urban planning process. The virtual way of getting informations is far more comfortable than the traditional one, to get informations at local authorities.

Crowdfunding campaigns offer a consumer-based approach to explore future planned urban designs. Released campaigns are used to transmit the designer’s intention to citizens. There is a public need to make sense of and draw a meaning from this complex nature of space design. Crowdfunded projects need to be explained in an easy-to-understand way in order to fulfill the donation goal. The urban space planning process becomes open to the public.

“The secret of crowdfunding is that it’s not about the money,” says Danae Ringelmann, co-founder of Indiegogo in a May 2013 article for Architect Magazine. “The true benefit of crowdfunding is being able to both validate an idea as well as engage a community. People are voting with their dollars. That’s why it’s so powerful for architects. It’s an effective way for them to test ideas for a place and, if successful in crowdfunding it, prove that people want it to come to life.” [21]

Platform serves as marketing tool

Cities, towns, regions and even countries are investing in branding campaigns in order to establish a reputation for themselves and to have a competitive edge in today’s global market. Branding campaigns are placed to define a picture of a city to target audiences. The expenses are mainly about exploring the relations between citizens, symbols, meanings, and the city’s expression.

The physical characteristic of a city is mostly drawn by urban planners. Controversial the public interest is often very low. Architecture and its urban planning field is actually the most public of all arts. No one can remain to be affected by it. Therefore the question is rising why the common interest isn’t higher.

Architects and Urban planners are mostly rated by other architects and urban planners only. Concepts are mostly done and explained for experts and officials. This leads to a sort of experts’ language which is hardly to understandable for laymen.

Crowdfunding could reform the public interest in urban projects and due to influence the reputation of planers and designers. The way of promoting a project to the public in a virtual interface, helps to close the gap between planners and users. The approach is to integrate the crowd in the selection and promotion process of creative projects and thus enable a new form of participatory development.

Crowdfunding is an interactive addition to traditional advertisement, like local press or expert’s magazines. It allows becoming part of a marketing strategy by participating in a small part of it.

Further, crowdfunding works as market validation. It is a method to test whether an idea or an intention fulfill the desire of the users or not. Dr. Phil Windley, an expert technologist, Executive Producer of IT Conversations and a serial entrepreneur, notes in a Forbes article, “The big payoff [to a crowdfunding campaign] is the information about the potential market we’ll get.”[22]

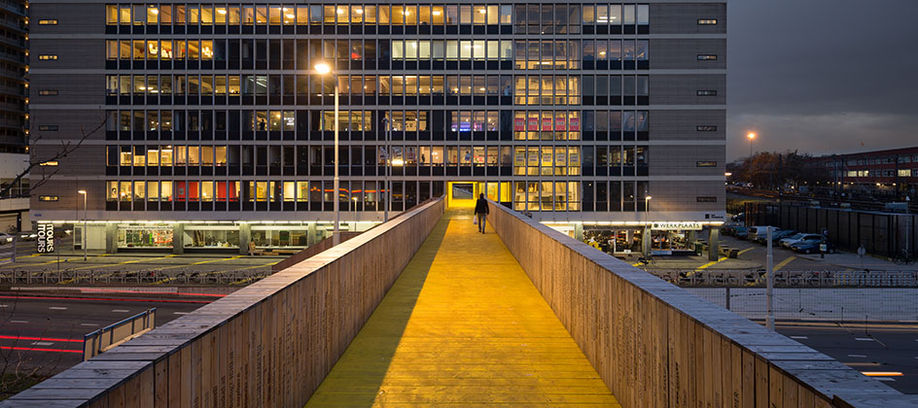

Expanding the us, iMake Rotterdam

A popular European urbanism project is running an international recognized campaign due to crowdfunding. Luchtsingel in Rotterdam benefits from global recognition and gains a high response on the marketing concept.

<youtube>yQAJj00Fv1A</youtube>

iMake Rotterdam is a city based strategy to strength the citizens awareness about their own responsibility. The tactic works through the personal touch. The subjective term ‘iMake’ underlines the shifted power. Authorities conferred influence to citizens. The possibility to shape the city ‘is mine’.

An active crowdfunding campaign is a good way to introduce a venture’s overall mission and vision to the market, as it is a free and easy way to reach numerous channels. Many crowdfunding platforms incorporate social media mechanisms, making it painless to get referral traffic to your website and other social media pages.

Typically, this allows ventures to receive thousands of organic visits from unique users and potential funders. These users are also important for viral marketing, as they have the ability to share and spread the word to their connections.

Crowdfunding as alternative way of funding

In view of the since 2009 lasting European financial crisis recent reforms lead to massive cuts in financial supports and to cancellation of projects in open space. The resulting austerity policy is to be blamed for the increasing privatization of public property, especially in Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal.

In general the budgetary situation of cities and communities are in a critical position nowadays. Public expenditures are limited and the process of distribution seems complicated due to bureaucratic restrictions.

Public culture promotion (including regional development) can get support through crowdfunding, in order to increase the budget. This new model of collaborative crowdfunding already exists. A pilot project will start in 2015 in several German cities, organizing urban projects by public funding with city authorities behind.

About the fact of using privat funds in order to cover public resources, the former New York City Parks Commissioner and current senior vice president at the Trust for Public Land Adrian Benepe says: "[r]ather than exacerbating inequality, private money enables a city to take public money and allocate it to neighborhoods that have no chance to do private fundraising."

In New York City, he says further, “public agencies can’t proceed until all the money is in place. So in that way, private money can either get projects started or wrap them up, like with the Hampline or Paine’s Park. It can be the last piece or the first piece, but at a standard price of $1 million per acre for an active recreation park in most American cities, it’s unlikely to be the whole piece.”[23]

The Hampline, Memphis

In cities where the municipal budget situation has not permitted adequate investments, the process of giving might be useful.

In Memphis many neighborhoods have deep needs but shallow pockets.

Asked whether in his time in parks he saw large, multi-million-dollar projects sit unstarted for want of When ioby crunched its own data last May, it found that 65 percent all projects were in low-income neighborhoods, and in some areas, like Memphis, the majority of projects were in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty where median household income is below $20,000.

In Davies’ next paper, he points both to a crowdfunding campaign to subsidize Google Fiber in lower-income parts of Kansas City, and to one in Oakland that paid for private security in an affluent neighborhood, giving residents there greater access to public safety than what other parts of town could afford. [24]

The Paine's Park, Philadelphia: a funded skatepark

The city of Philadelphia is using crowdfunding to pay for projects when it lacks funds.

The city could raise $10.000 to cover a cost overrun on a public skateboarding park due to a Kickstarter campaign.

From the organizers point of view:

The forthcoming Franklin’s Paine Skatepark has also leveraged crowdfunding to support its final stage of construction. It will be the largest public skate plaza in North America. The total project cost is about $4.5 million, but there's still miscellaneous funding needed.

The skatepark has been in the works for 10 years. The location is in Fairmount Park along the Schuykill River banks, near Martin Luther King Drive and Ben Franklin Parkway.

The Franklin's Paine Skatepark Fund is using Kickststarter to raise $10,000 to cover outstanding “soft costs” that have come up, such as construction and management costs that their funding sources didn’t cover. Executive director Claire Laver said, “With eight days to go, we’ve surpassed our goal. We are certainly excited about that.” Their kickstarter campaign solidified the final project needs, and a ribbon cutting is anticipated this May. Public parks often relied on support from donors. Crowdfunding distributes the responsibility from single donors to a crowd. It is possible for anyone to give whatever they can. [25]

Claire Lever continues: “We see a lot of opportunity for supporting and cultivating innovation inside the city in things that you might not want taxpayer dollars to flow directly to. It provides a little bit of flexbility-- when you have multiple sources of funding.” [26]

The Low Line, New York City

<youtube>l-jKuJIT34I</youtube>

In Manhattan, a non-profit raised $100,000 for the LowLine, a sunlit underground park that, if fully funded, would run below the Lower East Side of Manhattan in a historic trolley terminal.

Risks of crowdfunding in the urban planning process

The concept of crowdfunding has become a formidable new source of funding for a variety of use cases. In 2013 the global crowdfunding industry was responsible for $3 to $5 billion of funding.[27] But before declaring crowdfunding as the potential 'answer for everything', also risks should be considered.

Fraud and suspicious intentions

Fraud occurs in every type of activity that involves money. The risk of fraud in crowdfunding seems larger, because normally the investor does not get in touch with the entrepreneur. Further the lack of specific knowledge of the business idea could be a weak point. Many parts of a business venture may difficult to quantify particularly by someone with no financial or business experience.

In general the motivation behind project funding is categorized by three different types: social, material or financial. In consequence it could be said, crowdfunding may attract also those who are looking for personal benefit rather than for shared values.

Different kind of fraud should be noted as possible in crowdfunded urbanism, in order to the case study of CJ Cornell and Charles Luzar. [28]

Preempted fraud

In 'Preempted Fraud,' a suspicious crowdfunding campaign is shut down by the platform before any money changed hands. The policing are often done by members of the site. Discussion often happens in public forums and platform administrators are alerted. In these cases, the escrow-protected nature of fund exchange proved an important safeguard for those backing a campaign.

Stillborn fraud

'Stillborn Fraud' occurs when a campaign that is submitted for launch is summarily rejected by the platform. While campaigns are rejected for a variety of reasons ranging from technical errors to merely being incomplete, there are certainly many that get rejected because they carry a risk of fraud. They are filtered out before they are ever launched.

Attempted fraud

Attempted fraud could take place due to a campaign using IP that they did not own, or similar misrepresentations. While these deliberate attempts often are ‘preempted’ or ‘stillborn’, several campaigns have been launched that have used copyrighted IP or have disputable claims.

Backer fraud

Project fraud is not limited to those raising money. There has been at least one reported case where a contributor has deliberately pledged money to crowdfunding campaigns with the intent to withhold the funds or to file a claim to get their money refunded.

Backer-Creator fraud

Project creators have contributed to their own campaigns either directly or through surrogates. This is further a gray-area since the intention may merely be to demonstrate some funding momentum or to ‘put the project over the top,’ but the crowd will sometimes respond negatively to this practice if they can even detect it.

Broker/Portal fraud

Crowdfunding has spawned hundreds and thousands of niche platforms – and thus increases the chance of fraud and other malfeasance. With a great number of different platforms, the risk raises that portal operators may engage in fraud, or enable fraud.

Costs in an urban scale cannot get covered

Hidden costs

Hidden costs means everything beyond formation charges. In general, the operation costs of a built project are difficult to estimate. To fund the required money to kick-start the building process won’t be enough. A built project for example demands a security and facility management. The question about responsibility in the next decades needs to be answered.

Funded budget

To cover the costs of an urban and infrastructural project a lot more backers are needed in order to raise the required money. Direct crowdfunding seems unrealistic when it comes to major urban planning processes like infrastructural projects.

For smaller initiatives with maximum costs about approximately $20.000, crowdfunding has proven their success, as in the article ‘100 projects’ listed. Higher expenses are naive by now. According to the forbes magazine, the most successful business crowdfunding campaign was about to fund the Pebble E-Paper Watch, which raised $10.266.845 in 37 days. [29] For the sake of comparison: expenses in an infrastructural scale easily rise about $800.000.000.

Nevertheless, the potential of funding by a crowd is not been exploited by now. The number of participants is still growing.

“Crowdfunding is off to an even stronger start this year with an expected industry growth rate above 92% in 2014. Every day, more entrepreneurs are turning to business crowdfunding to get their creative ideas and early stage companies off the ground.” [30]

+Pool, an on-going feasibility studie

The public space project +Pool is a crowdfunded floating swimming-pool, located in the New Yorker East-River. The cross-shaped pool would be used to clean the water while providing a public space.

<youtube>JqZTlPrYf38</youtube>

The first goal of $250.000 could be reached on Kickstarter in July 2013, which enables the team to build a prototype and to continue with feasibility studies.

In the teams point of view:

“A huge and essential milestone in getting + POOL closer to the water is being able to test all the filtration materials in real-river conditions. To do that, we'll be building a mini, temporary and floating science-lab version of the + POOL that we're calling Float Lab. The Lab will allow us to test a combination of different materials right in the East River and assess the water quality across 19 different parameters, ensuring clean and safe water for swimming across all standards.” [31]

The catchment area counts

The common strategy of crowdfunding platforms are entirely oriented towards a global attention.

The ‘catchment area’[32] describes the geographic area in which funders may be interested in funding a project. In urban matters, the catchment area gets smaller, which means the value of the average contribution goes down. As a consequence, cities with high populations are better positioned to crowdfund urban initiatives.

In global metropolis like New York City, London, Berlin or Amsterdam local projects could get support from non-resident backers. “Because of its connectivity, a place like NYC has a long tail to draw funding from. In a large, well-connected city the crowd is more crowded.”[33], Dan Hill and Bryan Boyer point out. In those specific cases the catchment area is widening. For the proposed +Pool, the specific location supports reaching the goal.

Cities which do not meet the requirements, such as popularity, population and connectivity, will not be suitable for crowdfunded urbanism, but can instead likely benefit from Crowdsourcing urbanism.

“The catchment area is less relevant for crowdsourcing, the collective gathering and vetting of ideas. Instead of using an online platform to attract funding, smaller cities will likely find more benefit from using platforms to involve citizens in equitably distributing funds and in developing proposals together for how the city may be reshaped.”, Brickstarter proposes.

Global action, local impact

One of the most interesting parts in crowdfunding is the global interaction between users and entrepreneurs. When it comes to crowdfunded urbanism this effect needs to be limited, in order to launch serious campaigns with social intention behind.

As the following example will show, global crowdfunding can impact local changes, which underlines the conflict of interest.

Robocop Statue, Detroit

Detroit in Michigan is still suffering from diverse financial crises. After the automobile industry moved away, the financial situation of the city collapsed. Detroit draws the picture of a ghost town with its emptiness. With at least 70.000 abandoned buildings, 31.000 empty houses, and 90.000 vacant lots, Detroit has become a playground for many urban utopians.

In 2011 more than $67.000 could be raised on kickstarter in a six-day campaign with the intention to erect a bronce statue of the science fiction hero Robo-Cop in honor to the 1987 released movie in which Robo-Cop fights against crime in future Detroit. [34]

The campaign got donations from around the world. A majority of the funds, $25,000, came from graphic designer Pete Hottelet of Omni Consumer Products, a San Francisco company named after the fictional corporation which builds RoboCop in the film.[35]

Succeded campaign does not guarantee building permission

The legal framework is one of the most difficult parts in crowdfunding built environment. The practical reality of the planning procedure is a frustrating, slow and complex process. A slow-moving bureaucracy can jeopardize an already-funded project. The lack of specific knowledge and especially the complexity of building permissions increase the risk of failing due to administrative barriers.

The section Legal Situation will give a detailed overview about the current law situation in the German-speaking area.

Legal situation

Definitions

BUILDING LAW

The public building law contains all the regulations which affect the use of the ground, what is built on the ground, whatever is removed or altered. The private building law regulates the interests of ground owners. [36]

PLANNING LAW

The entity of regulations that focus on urban and regional planning, land use regulations, building planning and the legal effects of all these laws.

The building- und planning law situation in central Europe

The building industry is regulated by a number of laws. The developement of residential areas and the construction of buildings is regulated by the public administrative law. Those laws often set limits to the interests and designs of constructors and ground owners. The construction of a new building needs to be notified in order to be in accordance with the building laws. The individual building permit is the lowest in the hierarchy of construction regulations. According to our definitions, a urban crowdfunded project is a individual building project. [37]

Justin McGuirk from The Guardian puts it in a nutshell: "The big difference between Kickstarter projects and public space proposals is that the latter will require local government approval. If you can prove that a community is behind your project, it will help you make a convincing case to the local authority. And if that community also decides to fund it, what an infinitely more persuasive proposition."[38]

Who is responsible

Since the constitutional law in Austria does not regulate the construction and regional planning law, all the building regulations are beeing handled individually by the provinces and not the state itself.

Public and private building law

The building law can be devided into two sections: the public and the private building law.

The public building law contains all the regulations that focus on the use of the ground, what is built on the ground, whatever is removed or altered. These regulations aim to retain public interests.

The private building law contains all the regulations that focus on private property, neighbor laws, contracts, liabilities etc. The use of the ground is genereally a matter of the ground owner. He is able to do whatever he wants with his property as long as his interests are covered by the constitutional law (which of course includes the building and planning law) and don't interfere with public interests.

What needs to be notified, what doesn't

Certain buildings such as military facilities and energy producing structures are not included in the constitutional law. The construction of such facilities is possible without a permit. [39]

Needs to be permissioned (a building permit is neccessary)

- new buildings and additional buildings

- demolition of buildings

- change of use of a building

Needs to be notified (the public autorities need to be informed and have to accept)

- additional buildings to annexe

- safety walls

- safety roofs

How can be built in public space

The decisions of a individual planner without any legal regulations would probably lead to a building and area developement which is not covered by public interests. Not only important rules/aims to retain the common good would be in jeopardy, but also the prevention of any dangers and other social matters need to be retained. The regulations in the building and planning law say that buildings/Therefore buildings

- can not be erected in unsuitable places

- need to have a low use of resources

- can not interfere with the overall appearance of a place

As a result it can be said, that the aim of the building and planning law is to enforce these regulations when it comes to a (individual) construction activity. The common good needs to be preserved and the building and area developement has to happend in the best way possible.[40] The well known case of the Robocop statue in Detroit is a good example of how crowdfunded projects in shared spaces might lead to a conflict of interests

Who decides what can be built

The execution of the building and planning law regulataions are handled by various institutions. Austria as an example: The first instance in a municipality of Austria is the Mayor. The second instance would be the municipality council. In the city of Vienna the urban administration (Magistrat MA 37, also known as construction-police) is the first instance. The decision making and evaluation of certain interests of constructors, designers, ground owners, etc. by these institutions are limited by the discretion of the legislative organ. This means, that the building and planning authorities need to follow the existing laws in form and content.[41]

Crowdsourcing in Public Spaces

Main article: Crowdsourcing Urbanism

Nowadays the concept of urban planners, developers and politicians turning to citizens to detect their individual needs, wishes and ideas regarding the revitalisation of specific areas is well known. One downside that occurs is that at some point it has also become a tool of handing the responsibility over to larger anonymous groups by outsourcing intricate decisions to public opinion polls. This ambivalent process has to be questioned to the point of spotting hidden pretences of the initiators of such surveys. Although these political driven urban renewal processes can be seen as part of the Crowdsourcing Urbanism movement there are distinctively smaller projects that are closer to the roots of everyday problems. In many cases those ventures bypass the abovementioned issues by having a direct citizen-led approach to crowdsourcing in urbanism in spotting, naming and changing facets of current controversial subjects. By the lack of monetary motives and indirect cash flows those projects have a faster and more straightforward method on altering the urban tissue. The source of motivation seems to be created by urgent needs of locals that in some cases try to improve their daily lives by making smaller modifications to the district they live in. There’re projects that blur the lines between vandalism, street art and legit urban upgrading and one of the biggest concerns can be seen in the ignoring of laws and regulations. At the edge of underground street art and self-proclaimed idealism this movement forms the basis of individuals and smaller groups that have the drive to actually contribute in their own way to their surroundings. Therefore the important issue of undemocratic decision making has to be addressed, because by having smaller groups imposing their very special ideas of reshaping the area by not including a vaster amount of people into the procedure can create the impression of autocratic tendencies and eventually cast a bad light onto those reformative notions.

Prospect

The connection between crowdfunding and urban development is getting stronger. The applicability of crowdfunding on urban space plays a minor role in the previous analysis of the topic. Crowdfunding Urbanism is not yet comprehensively considered. Crowdfunding is rather examined as a financing instrument in general or in relation to other subject areas (Kickstarter, journalism, etc.). Fundamentally, the question of transferability of crowdfunding projects on urban development, which usually differ in their complexity and their impact on typical Kickstarter projects. How should existing models of crowdfunding be adapted in order to be applied in city-based projects?[42]

The urban researchers Dan Hill and Bryan Boyer are the pioneers in this field. In their book BRICKSTARTER they present a new form of platform for crowdfunding urbanism. They believe it is necessary to realign communal decision-making on public space. Instead of state-institutionally organized citizen surveys, where rejection of projects is regularly expressed, the active organization, discussion and support of projects should be possible.[43]

Scenarios

During the research work for the legal situation in Crowdfunding Urbanism many questions emerged. These questions are being illustrated with fictional scenarios which are inspired by actual events.

Scenario A

A public space in a city needs to be revaluated. The officials announce a competition where urban planners, architects, sociologists, etc. can contribute their plans for the reconstruction. The authorities choose the best designs, present them to the public and ask for feedback. The design which suits the common interest best is then beeing realised. A good example of how this scenario can go wrong is the revaluation of the Mariahilferstraße in Vienna. The outcome of the project was very confusing to the public and led to protests, which made the authorities overthink their decisions. Eventually a solution was found.

Scenario B

A private person has an idea to improve the situation in a shared space. The idea could be to build benches on a empty plaza or plant trees and bushes to revaluate the space and make it more accessible to the citizens. Since it's hard do execute such a project alone, the person gathers a few other people and they form a group. The group works on material to put on a urban crowdfunding platform in order to access a bigger crowd. The project is a huge success, people seem to love it and donate money. Eventually enough money is raised to realise the venture. Now the difficult part begins: The team has to present their ideas to the authorities in order to get permission to actually carry out their plans. These authorities consist either of a committee or a single person that can decide about the fate of the project.

A statement by Bryan Boyer and Dan Hill of Brickstarter describe this situation pretty well: „Just because a project is funded does not mean that it has passed all of the permitting and regulatory hurdles that it may need to clear.“ [44]

Very questionable about this scenario is the fact, that the fate of a project which is backed by a huge number of people is pending on a single person, or a committee. A good example of this scenario is the famous case of the Robocop statue in Detroit. On his Twitter page former Mayor Dave Bing states that „There are no plans to erect a statue to Robocop. Thank you for the suggestion.“[45]

The statement by Jocelyne Bourgon concludes this paragraph perfectly: „We are facing 21st century problems with the inflexible institutional silos of the 19th century.“ [46]

Scenario C

Officials realize that there is a problem with a shared space that needs to be solved in order to make it more attractive to the public. A city initiative is organised and the population is being asked for their feedback on how to solve the problem. Tools like Crowdsourcing and Crowdfunding grow in importance and authorities need to learn to use them and start interacting with the public. This is the logical way of handling problems in a modern government. People should be asked about their opinion and then contribute to solve the issue.

A good example for this scenario is the Luchtsingel bridge in Rotterdam. On their website they state: „In 2011 the Rotterdam City Council organised a city initiative, an administrative instrument for public participation to encourage reform. Inhabitants of Rotterdam were called to present projects for the revitalisation of the city. To enrich the quality of life in city projects. 4 million euros from the city initiative is a set aside for on project implementation.“ [47]

CONCLUSION

As long as the official institutions remain as inflexible as described in scenario b, people will have to use tools to bypass existing rules, restrictions and regulations. „Brickstarter is just such a tool: it is a Trojan horse that infiltrates the “dark matter” of bureaucracy, enacting change from the inside.“ [48]

Practical Experience

Stay Tuned

In terms of structure of crowdfunding platforms in urban context, not only the motivation of the funder is important, but the motivations of initiators are interesting also.In the Netherlands, architects are taking the initiative and coming up with new strategies to counteract the crisis in their work area.[49] ZUS architects are using the new hype of crowdfunding and setting it in public space for their own ideas. A 350-meter long wooden bridge spans between two districts. One of these neighbourhoods is suffering from social exclusiveness. The intention is to solve the situation due to building a connecting bridge. The funding will be secured by the sale of wooden boards, in which the name of the respective benefactor is engraved. This project makes clear that interested citizens only have a financial part in it.

The project is sufficiently developed and advanced, so that it only needs to be financed. The state treasury is empty and as an alternative investor citizens can be used. It is important to choose a proper strategy, so that the interest in the project of the investor is still there and in further steps to move him to finance the project. Different incentive structures of crowdfunding platforms, make the platform-users investors. Understanding this motivation is important for the selection of the appropriate instrument and for the success of a crowdfunding campaign. The emotional connection between the investors and the project is also very important for the success. A well-organized crowdfunding campaign is working due to the traditional marketing model known as the AIDA principle. Attention, Interest, Desire, Action.

The sense of belonging in a community, the responsibility for one’s own environment and the social responsibility are guiding terms that connect public life and the space in which it takes place. Everyone feels automatically responsible for existing problems and social exclusion, as described in the example, and it raises the need to help. The purchase of a wooden board is already kind of help. The task of the home country, to protect, to help and to watch over the city, to manage the resources and to solve social problems, is now the task of the community and participating actors. Citizens are asked to pay up in a very gentle and playful manner. If the community already takes part in funding, the potential of a crowd is certainly even higher.

What about us

The Detroit example with the Robocop Statue shows the importance of balance between global participation and local impact. It should be protected against dubious initiatives. The dubiousness is strengthened by the unilateral, favorable choice. Either one finds the project good and has the opportunity to invest in the project or one ignores it and hopes for the dogmatic decision of the Mayor, who cares for the face of the city and will stop the project.

Such thinking would contradict to the Laclaus and Mouffes discourse about post-Marxism hegemony theory. The public community is strengthened by conflicts and different opinions. The more conflict the more public - less consensus.[50] If I disagree with the project, I would like to have a valve in order to express my displeasure. A certain number of "likes" and amount of collected money is regarded as a democratic decision. The public space is a platform in which a "dislike" should have space. A "dislike", which is not marked out of spite and bad temper, but shows a desire for an alternative solution. Furthermore, it is the worldwide participation and interest in issues related to the local context. We do not limit ourselves by our immediate, noticeable physical environment where our neighbors are already regarded as outsiders. Our environment is the world, and the border is widely extended. But does our mental perception relate to our physical world? Should an outsider from the Internet decide about our environment or should it be the neighbour? The “Stadtmacher” has an answer to this question and limits the possibility of starting an investment on local environment.

We can do it

One of the major goals of crowdfunding campaigns, besides the financal part of the project, is to build a network of supporters. Projects that are planned in urban areas bring along a large number of actors. There is a need for new communication methods between the actors of urban development. Crowdfunding platforms can contribute. It is known that the variety and diversity of urban development stakeholders is identified and the communication difficulty between the actors is highlighted. Even more surprising is the lack of tools that could help to organize an exchange between planning authorities, the private and the public.[51] As a consequence, decision-making processes on the development of urban space are perceived as not open and difficult to read. A platform that allows communication between various stakeholders would clarify this kind of processes and make them open for interested people.

„STADTMACHER“ is a project of the Urbanista group that deals with the communication and mediation work between different actors. They are already one step ahead. „Stadtmacher“ has recognized that a large potential lies not only in funding by a crowd, but also in the crowd itself. The concept of crowdfunding should be seen as a form of crowdsourcing, in which the resources of the crowd can be used for ideas, feedback and possibility to generate solutions to specific problems. Cognitive force of a crowd would improve the development process of a project. Crowdfunding as a new instrument should be understood as a participation-based urban development.

The idea behind it is as follows: „Stadtmacher“ is a platform for civil projects in public space. Project ideas for your own city are submitted on this platform and go through several stages of development until the possible implementation of ideas. The special feature of this strategy is that no one is left alone with their own idea. Along with the „Stadtmacher-Team“ the ideas are developed and launched towards implementation - both through expert advice and by building a crowdfunding platform through which the first steps as well as the entire project can be financed. “Achieving success in five steps”[52] is the promise of the „Stadtmacher“-Team. But if you take a detailed look, it gives the impression that the success of the project is not guaranteed. The euphoric initiative of citizens to participate actively in urban development is hampered by many bureaucratic barriers and official hurdles. Should the project fail because of the legislation?

Next Steps

„The new stage in crowdfunding is all about civilians directly funding and marketing public goods, making their own neighborhood, village and city more attractive.” New York Times

After the initial investigation of the topic and more detailed analysis of many aspects, we discovered that it takes some more time and research to generate a working platform for crowdfunding in public space. An urban crowdfunding platform should be able to respond flexibly to the needs of the individual case and support the development and adaptation of crowdfunding instruments. In many German cities the popularity of Crowdfunding Urbanism rises and already notes first successes. Vienna, for example, promotes citizens to stand up for their own city and to shape it.[53] Thus, crowdfunding is intended as crowdsourcing Urbanism and shows a new, perhaps pioneering side.

One of the sectors where we believe crowdfunding could play a positive role is in the local governmental sector. Municipalities have been, in the more recent decades, integrating participatory tools into their urban planning frameworks,these tools are being used to foster a more direct relationship between citizens and their urban environment. Crowdsourcing is a natural fit for these types of processes (Brabham, 2009), by using social media and other avenues municipalities can “call to action” a large number of interested citizens to participate in the design of ongoing municipal projects or even propose new ones such as the example of Stevenson square in Manchester. Most participatory budgets, where citizens propose their own projects, can only fund a small percentage of the proposed projects but by using crowdfunding the municipality could boost available funding and increase the amount of funded projects. Municipalities could also run their own crowdfunding platforms continuously instead of integrating them into seasonal budget actions. These platforms would increase the visibility of public participation in urban planning and could generate, besides funding, increased awareness and interest in the urban environment.[54]

Literature

- Tayfun Belgin (Hrsg.): Christine und Irene Hohenbüchler – ... ansehen als ..., ... regarding as ... König u. a., Köln u. a. 2007, ISBN 978-3-9502333-0-8.

- Dorothee Messmer, Markus Landert (Hrsg.): Wilde Gärten. Christine und Irene Hohenbüchler. Niggli, Sulgen u. a. 2004, ISBN 3-7212-0523-5.

- Laclau, E./ Mouffe, C. (1985), Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. Towards a Radical Democratic Politics

- Laclau, E./ Mouffe, C. (1991): Hegemonie und radikale Demokratie. Zur Dekonstruktion des Marxismus. Wien

- Boyer, B.; Hill, D. (2013): Brickstarter. Hg. v. R. Hyde. Helsinki Design Lab, Sitra

- GB6/14/15, DIY Stadtanleitung, Magistrat der Stadt Wien, Mai, 2014

- Ole Brandmeyer, C. (2014) „Crowdfunding Urbanism“, Schwerpunktarbeit, TU Berlin

- Correia de Freitas, J. Amado, M. Crowdfunding in urban planning Opprtunities and Obstacles, Report, 2013

References

- ↑ http://business.financialpost.com/2013/01/17/indiegogo-founder-advises-startups-not-to-wait-for-perfect/?__lsa=485d-fb39

- ↑ http://www.forbes.com/sites/tanyaprive/2012/11/27/what-is-crowdfunding-and-how-does-it-benefit-the-economy/

- ↑ Jeffrey Hou, Benjamin Spencer, Thaisa Way, Ken Yocom, Now Urbanism: The Future City is Here (Routledge, 2014).

- ↑ http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english-german/crowd_1

- ↑ http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/fund

- ↑ https://www.planning.org/greatplaces/spaces/characteristics.htm

- ↑ en.wikipedia 5/08

- ↑ Carr u.a. 1995, S. 3

- ↑ http://www.thefreedictionary.com/NIMBY

- ↑ http://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/yimby

- ↑ http://ioby.org/

- ↑ http://occupywallst.org/about/

- ↑ John L. Hammond, The significance of space in Occupy Wall Street, Interface Journal 5, November 2013

- ↑ John L. Hammond, The significance of space in Occupy Wall Street, Interface Journal 5, November 2013

- ↑ Peter Marcuse, Occupy and the Provision of Public Space: The City's Responsibilities.

- ↑ https://innovation.mfg.de/de/standort/digitale-trends/internet/studie-zur-digitalnutzung-im-deutschsprachigen-raum-1.30734

- ↑ Michel Callon, Pierre Lascoumes, Yannick Barthe, Acting in an uncertain world: An essay on technical democracy, MIT Press, 2011

- ↑ Michel Callon, Pierre Lascoumes, Yannick Barthe, Acting in an uncertain world: An essay on technical democracy, MIT Press, 2011

- ↑ Dan Brown, Conversation with Rodrigo Araya, Tironi Asociados, Chile, April 23, 2012 (http://brickstarter.org/conversation-rodrigo-araya-tironi-asociados/)

- ↑ Dan Brown, Conversation with Rodrigo Araya, Tironi Asociados, Chile, April 23, 2012 (http://brickstarter.org/conversation-rodrigo-araya-tironi-asociados/)

- ↑ Dan Lear, Crowdfunding Architecture: Not about the money?, Make Architecture happen, March 13, 2014 (https://www.makearchitecturehappen.com/blog/crowdfunding-architecture-not-about-money/)

- ↑ Dr. Phil Windley, Could Crowdfunding replace traditional marketing?, Forbes Magazine, October 20, 2013 (http://www.forbes.com/sites/cherylsnappconner/2013/10/20/could-crowdfunding-replace-traditional-marketing/)

- ↑ Brady Dale, Crowdfunded Parks are coming and that isn’t a bad thing, Next City, November 20, 2014 (http://nextcity.org/daily/entry/in-public-crowdfunding-parks)

- ↑ Brady Dale, Crowdfunded Parks are coming and that isn’t a bad thing, Next City, November 20, 2014 (http://nextcity.org/daily/entry/in-public-crowdfunding-parks)

- ↑ Sarah Glover, Philadelphia uses crowdfunding to complete civic projects, NBC Philadelphia, march 27, 2013 (http://www.nbcphiladelphia.com/news/local/Philly-Projects-Crowdfunding-200081891.html)

- ↑ Sarah Glover, Philadelphia uses crowdfunding to complete civic projects, NBC Philadelphia, march 27, 2013 (http://www.nbcphiladelphia.com/news/local/Philly-Projects-Crowdfunding-200081891.html)

- ↑ Sonya Gulati, Crowdfunding: A kick starter for startups, Special report TD Economics, January 29, 2014 (http://www.td.com/document/PDF/economics/special/Crowdfunding.pdf Accessed December 14)

- ↑ CJ Cornell, Charles Luzar, Crowdfunding fraud: How big is the threat?, Crowdfund Insider, March 20, 2014 (http://www.crowdfundinsider.com/2014/03/34255-crowdfunding-fraud-big-threat/ )

- ↑ Wil Schroter, Top 10 Business Crowdfunding Campaigns of all time, Forbes Magazine, April 16, 2014 (http://www.forbes.com/sites/wilschroter/2014/04/16/top-10-business-crowdfunding-campaigns-of-all-time/)

- ↑ Wil Schroter, Top 10 Business Crowdfunding Campaigns of all time, Forbes Magazine, April 16, 2014 (http://www.forbes.com/sites/wilschroter/2014/04/16/top-10-business-crowdfunding-campaigns-of-all-time/)

- ↑ https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/694835844/pool-tile-by-tile

- ↑ Bryan Boyer, Dan Hill, Brickstarter, Helsinki Design Lab and Sintra, 2013

- ↑ Bryan Boyer, Dan Hill, Brickstarter, Helsinki Design Lab and Sintra, 2013

- ↑ https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/imaginationstation/detroit-needs-a-statue-of-robocop

- ↑ Sara Malm, Giant bronze RoboCop statue to be unveiled, Daily Mail Online, September 26, 2013 (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2432927/Giant-bronze-RoboCop-statue-unveiled-Detroit-crowd-funding-raises-67-000-days.html)

- ↑ https://www.help.gv.at/Portal.Node/hlpd/public/content/99/Seite.990084.html

- ↑ Arthur Kanonier, Arbeitsunterlagen zur VO „Bau- und Planungsrecht“ (Austria: Vienna University of Technology, 2012).

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/aug/24/brickstarter-crowd-funding

- ↑ https://www.help.gv.at/Portal.Node/hlpd/public/content/226/Seite.2260200.html

- ↑ Arthur Kanonier, Arbeitsunterlagen zur VO „Bau- und Planungsrecht“ (Austria: Vienna University of Technology, 2012), VO 1.

- ↑ Arthur Kanonier, Arbeitsunterlagen zur VO „Bau- und Planungsrecht“ (Austria: Vienna University of Technology, 2012), VO 8.

- ↑ Ole Brandmeyer, C. (2014) „Crowdfunding Urbanism“, Schwerpunktarbeit, TU Berlin

- ↑ http://www.urbanophil.net/stadtentwicklung-stadtpolitik/crowdfunding-urbanism

- ↑ Bryan Boyer and Dann Hill, Brickstarter (Finland: Sitra, 2013), 25.

- ↑ https://twitter.com/davebing21/status/34698788601860096

- ↑ Jocelyne Bourgon, A New Synthesis of Public Administration: Serving in the 21st Century (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011), 91.

- ↑ http://www.luchtsingel.org/en/about-luchtsingel/the-city-initiative/

- ↑ Bryan Boyer and Dann Hill, Brickstarter (Finland: Sitra, 2013), 6.

- ↑ https://annekebokern.wordpress.com/2011/11/16/crowdfunding-brucke-in-rotterdam

- ↑ Laclau, E./ Mouffe, C. (1985), Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. Towards a Radical Democratic Politics

- ↑ Ole Brandmeyer, C. (2014) „Crowdfunding Urbanism“, Schwerpunktarbeit, TU Berlin

- ↑ http://www.stadtmacher.org/#stadtmacher-startet-im-februar-2015

- ↑ GB6/14/15, DIY Stadtanleitung, Magistrat der Stadt Wien, Mai, 2014

- ↑ Correia de Freitas, J. Amado, M. Crowdfunding in urban planning Opprtunities and Obstacles, Report, 2013

(enter the word "references /" in two < >and this register will be created automatically, if you always used "ref" in two < > for your quotes and references in your paragraphs. If you still don't know how to use references, take a look at the backend.)