From criticality to creativity: a Neoliberal word snake

Contents

[hide]This investigatory attempt into the sphere of contemporary art and in close reference to emerging creative practices, i.e. crowdfunding, considers the conceptual textiles in which the older space for criticality has been slyly overcrowded with a more incorporated set of collocations rotate around the systemic enforced creativity. In current juncture, without the space of further outside to exercise our self-reflexivity, the aim of building up this glossary is to demarcate how we can still talk about criticality in current economic immanence. The idea is, the more variable the glossary can be, I suppose, the bigger fissure it would be opened for us to re-empower the role of criticality and to navigate the intellectual direction in the neoliberal transit.

Creativity–Criticality

Creativity in criticality

In a Foucaultian ideal, criticality is not a simple action that one performs one’s power through judgment. It is more related to a sense of making, by which a two-fold manner of inhabitation is created: One lives in an intellectual space that is created outside of the domain where authorized knowledge is produced and operating; though on the other hand, one nevertheless inhabits within the original space where authorization take place and where one’s critique is touched upon.[1] As suggested above, criticality has to do with the action of making––a secularized substitute for creating. Therefore, a critical action implies a spatial creation. It is in this sense that the ontological agenda of creativity is a core factor within the composition of criticality.

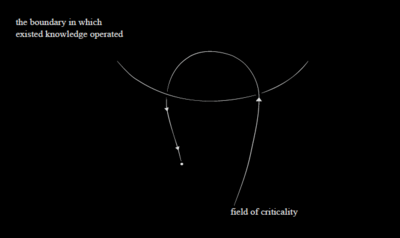

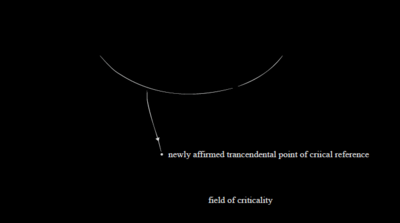

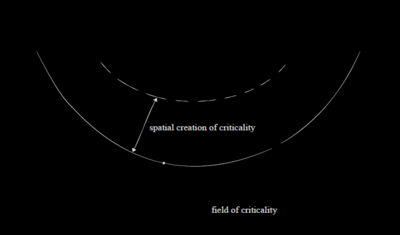

If we first draw a line to shape the inside and the outside regarding the field of knowledge, therefore, above concept can be pictorialized as below:

1)

2)

3)

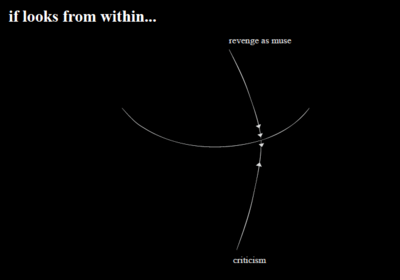

Criticality in creativity

If taking the vintage point from creativity and considering its relationship with the vanishing point that is criticality, the supporting example then should be those akin to what Berlin-based critic Jan Verwoert once denoted, ‘vengefulness as muse’ [2]. It depicts Dostoyevsky’s conception of such bond, that: ‘the desire to take revenge (for an injury, a moment of humiliation, a painful criticism once received…) may be one of the most powerful driving forces behind the urge to write, to create, to make art.’ (ibid.) In such example, criticality serves as an internal impulse for generating creativity.

Creativity absorbs criticality

The financial capitalization and capturing of creativity via advertising slogans

By juxtaposing the two relationships denoted in last respective statements, the axis of criticality-creativity therefore can be understand as a reciprocal relationship. Though such organic reciprocity has gradually been broken in the sense that creativity been magnified and utilized while criticality is undermined, and in some cases been substituted with other words, therefore reinforced into the glossaries created by the financial capital. Such impulse has been made explicit in British artist Carey Young’s video Product Recall, where she lays in a psychoanalyst’s couch, recalling 20 some corporate slogans that rotate around ‘imagination’ or ‘inspiration’. This rhetorical control for consumers’ mnemonic system tellingly states the easily assimilate nature of creativity, while leaving its traditional counterpart, criticality, omitted. In an even more extreme example, Tirdad Zolghadr’s curatorial project Ethnic Marketing, critical oriented art learns from market strategy in order to understand the way in which criticality circulates in current system of academic and aesthetic economy.

The immanence of creativity

This is certainly true if we keep an eye upon the reality that art is increasingly democratized to an extent that we now have unprecedented population to make art, to visit art and to consume art—and more importantly, this transformation has made the creative population more governed by neoliberalist system. In this respect, the productive forces is not just from each individual’s singularity but neoliberal economy which reinforces and assembles its population’s creativity. An urgent plead around this issue has been famously made by artist Anton Vidokle and curator Tirdad Zolghadr with a performative lecture entitled A Crime Against Art (Madrid Trial). They accused themselves of being the colluder with bourgeoisie in the form of court, that there’s no outside for criticality to stand upon––even their creative putting of themselves into judgment cannot escape the destiny of loosing the ‘ideological opposition’ in which the criticality-creativity bind operates, thus inevitably running into a ‘critical vacuum’, voiced from the lawyer of defense, Charles Esche. Here, the lost of free spaces for producing art renders criticality into the immanence of creativity. [3]

Criticality–Risk

Criticality with unmanageable risk

In ‘From Criticism to Critique to Criticality’, Irit Rogoff has once coined criticality as that which ‘acknowledges what it is risking without yet fully being able to articulate it’[4]. According to this formulation, criticality contains a sense of risk without being able to see its gestalt (since the utterer is inside, therefore at stake, therefore unmanageable). Following this, we can then see criticality as an equivalent of risk in the context of intellectual economy. We therefore acquire a new way to read Rilke’s formulation: ‘Works of art are always the product of a risk one has run, of an experience taken to its extreme limit, to the point where man can no longer go on’.[5] By substituting risk into criticality, and considering in relation to the creativity, which is an undissociatable part of making a work of art, we have the idea that risk is unmanageable, since risk happens while artists’ creation being taken to an extreme limit. This is more or less the classical idea about risk in art making. It runs without one’s control.

Pseudo criticality with pseudo risk

One of the obstacles for understanding creative practices nowadays is the problem in which its form appears to become identical to that of critical oriented art practices, while in essence remains highly different. For some, it may be characterized as ‘zombification’ of art[6], who acquired only the coating of criticality while the content remains hollowed. In come cases, the situation is even more extreme. Art aligns itself with creative markets and learn things from it. This may have its lineage in which art learns from everyday life in the 60’s, or from the legacy of relational art as well as research-based practices (90’s-2000), all the way to our previous case study: Ethnic Marketing curated by Tirdad Zolghadr. In order to look into art and creative practices while not blinding by the obstacles, one guideline for sharping one’s judgment is by inspecting into the discursive space each practices provided for criticality. And more effectively, one inspects into the space of risk taking. The latter can be seen as reified edition of the former. In such premise, one usually finds to kind of risks: one true risk, the other pseudo risk. To use previous example again, in A Crime Against Art (Madrid Trial), the witty performativity create a sense of tautology-liked paradox: its critical discourse asserts that there’s no longer the possible space of outside for one to exert critical action, so their practice is also entitled to be lack of an outside space that would potentially endangers the inside. It seems to be highly critical and reflect back to the utterer’s own symbolic position. One may say it’s a practice with critical stance, in self-reflexive fashion. But it’s also important to note that it is self-reflectivity without fatal risk—nothing would change, even the symbolic aspect of the art institution won’t, after all, one can also see the amusing atmosphere encompassing the trial as a feature of cynicism and nihilism. In this respect, it won’t be unfair to claim such immaterial artistic practice as being pseudo-critical: it risks virtually nothing. Reflecting on the entire process in which art renders itself from concrete into immaterial, and in which art (in neoliberal terms specifically) becomes less harmful but more playful than ever, there is a broader spectrum in which such process can be found being embedded within the Post-Fordist result of ‘immaterial labor’, according to Michael Hardt, which ‘transform[s] other forms of production and forc[es] them to adopt its qualities’ [7]. Other way of delineation can be said as a process in which the viewing of art objects becomes the curating of artistic situations and participations (Claire Bishop).

Two different views on risk taking

Plato once famously claimed that the artist and poet should be banished from his ideal city of the Republic, since art is not loyal to truth, and the affective capability of poetry endangers the rule and order of authority. In such historical context, the artistic utterance is always already risky as it holds the capacity to intervene the political reality. But despite this long enduring idea of risk in art, we also have another register for understanding art and risk thanks to the maturity of art market. In an interview, Danish artist Michael Elmgreen from artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset once reflected about an artist friend of him, Dahn Vo. His commentary helps us to demarcate the role of the artist as well as the contour of currently market-boomed art world, reads: ‘Danh is an excellent poker player, very unsentimental in his approach to the game’, and he further explains that ‘[the h]istorical facts as well as the present reality or even personal context are his instruments, the cards in his hand, and the rules of the game are set by the art world itself’.[8] It is not a peculiar proclaim, since not only Elmgreen and his fellow artists, but also Isaac Julien once in Playtime (2014) uttered through the mouth of James Franco, playing an art adviser, that the practices in the art is ‘a game’. If one is to take such rhetorics granted, in which risk is entailed within the game of art rather than in the realm of life, then in this vein of being a contemporary artist, what one risks while making art is no more than playing out a wrong decision in a game. In comparison to previous notion of art and risk, in which the depth of risk is claimed to be unfathomable, now, the risk in a game is one that is to be managed. At worst, you loose the chip that you shown, but not your life. During the course of the transition from art making to game playing, the logic of art that once confronts with the rule but now seems to align itself towards financial game is explicit. More importantly, as the insurance market would broaden their potential clients, now the risk in art is under management. In other words, criticality can now be managed in the context of the financialized creative industry.

Risk–Faith

Risk management

Risk occurs to us when there are some factors that would potentially harm one’s interest. Identifying risk is then an important task to the field of finance and to all aspect related to the governance of lifes. Though to say risk is manageable, it is not saying one can reduce the chance of realizing a fatal event, but it’s about circumvention and deferring of risk by calling risk into the complex web of financing. To be clear, although risk is an uncontrollable factor, but its correlation with investment is amendable. Say, the degree of risk can be defined by calculation. Furthering this, a sufficient way to deal with risk would be that, as the neoliberal finance has tells us, one invests into such uncertainly rather than turning away from it—this is what one would referred as ‘risk management’. The way it is objectified by financial-capitalistic subject of investment is by a Derridean play of differing and deferring, i.e. to package the debt as a product and sell it, twice and thrice and potentially ad infinitum. Its internal logic is to create more credit to support and cover the unrealized expense materialized by risk, and such relationship is ensured by the time lag between the credit creation always ahead of the total amount of debt, which is one of the factor that produces risk. In another words, risk is deferred solely because of one invests faith on it, making the amount of faith slightly ahead of the amount of potential damage. The way in which faith accrues profit has been noted within many neoliberal case studies[9], but are we talking about a symbolic bound between different persons who shares the same interest when we talking about faith, or are we simply talking about a superstitious and Pre-Enlightenment kind of anti-intellectual faith, which game players would utilize to practice their trick? Before the idea of faith or belief being codified into financial market strategies and concretized into the concept of creditability, faith already plays a crucial role concerning not only the economy activity—even to that which Baudrillard termed ‘symbolic exchange’ based on Marcel Mauss’s analysis of gift exchange—but actually to all aspect of human activities that calls upon the notion of time and space. By testifying, persuading, verifying or even conjuring, whenever one refers to an unrealized stuff that is no loner existed or yet to come, or basically not being presence here and now, one brings it to our face by actualizing it with a form that known as ‘signified’. For example, one calls upon ‘apple’ that is not here by the word and picture. Speaking in this context, money and debt is based on such lineage of human activity of realizing the entity that is not here. Therefore, how a regime constructed solely by money and capital absorbs faith, reifies it into credibility for the use of creativity is a question worth to ask.

Faith–Credit

From the faith on criticality to the credit for creativity

In art and humanity, one keeps faithful to the capability of critical utterance. Such faith and faithfulness entails that one prevision a future in alignment with what has been done. Though in the context of creative industry within financial capitalism, it is artists’ credit plays an important role in order to maximize the resource for investing one’s production and reproduction. The task of faith now is to make the creditor believe what one capable of doing in advance, which suffice to the logic of funding rising, be it private or public, and more evident even when it comes to the more democratized form of funding alternatives. The key in neoliberal situation is to optimize your credibility, using it to undermine the critical situation that might be happening tomorrow. To be precise: risk, which means the decline of value in the future. Here, either speaking about risk or credibility, we are uttering on the ground of the temporality that has yet to come. Chinese-Swiss curator Li Zhenhua once launched a curatorial project How to collect contemporary art[10], which taps into the ambivalent zone between the much humanitarian ‘faith’ and the neoliberal ‘credibility’. The project mainly consists of a rule that runs throughout his project: he collects an emerging artist’s artworks—not based on the work he has seen or even heard, but on his personal understanding of the artist’s personality. The monthly transaction that supports the artist Zhang Lehua’s studio rent acquires works each time, but only kept in the box, kept folded until the day of Li’s curatorial project kicks off. In this project, the only bind that keep the curatorial relationship is therefore the curator-collector’s alleged trust on the artist, and renders the trust performative by unveiling the collections in the day of the opening.

Credit–Debt

Credit and debt

The more credit one is gathering, the greater amount of debt and indebtedness one is accumulating. Credit and debt are in direct proportion. But why barely any one fear of gathering debt? Debt implies an aspect of monetary presence, whereas one indebted to another more refers to a kind of symbolic exchange. The returning of debt can be postponed and delayed if credit gathered slightly ahead of it, whereas one can return their indebtedness by giving credit to the other. In the last analysis, as long as there’s no systemic inflation, a miracle of investment is true that one does not fear of debt as one constantly generate credit and accruing it with one’s creditors, a zero sum game into growth.

Credit–Interest

From disinterested pleasure to pleasure that generates interest

In the game of investment, the key is to gather interest (and lower the rate of interest as much as possible) based on one’s credibility.

Interest gathers investors that we refer as shareholders, whose investment returns in the form of share and its dividends or interest.

Such can be helpful for us to acquire different vocabulary to look into the aesthetic notion of interestedness. Though Agamben once talk about other kind of interest against Kantian notion of aesthetic disinterestedness. Via Artaud, Agamben maintained that it is the contagious character of art that made the authorities, say, Plato, banned art from the society in which they reign (or help to reign in Plato’s case). Therefore, we have another model of art with interestedness, without spectatorial distance but instead drawn from practitioner’s side. A triad: ‘threat–interest–practitioner’ replaced Kantian ‘pleasure–disinterest–beholder’.[11]

If we follow above financial vocabulary, and inspect into such triad with the game of investment as idea in mind, an updated formula trickily goes like the mixture of above two: ‘pleasure–interest–consumer (as the term included the beholder and the practitioner)’, which is certainly the case for our neoliberal condition. Say, one may pleasurably, or at least less critical than ever, participate into contemporary art scenes either in its artistic-productive way or the visiting-reproductive mode, both of whom consumes creativity which already disentangled from its previous correlation with criticality.

Postscript

The growing interest on art and creative networks results new forms of art and creative networkings, rendering the two alike to each other. To develop a glossary is to rethink the possible gap between them, with a hopeful intention to temporarily divorce them and sees the possible space for criticality. During the entire period, I locate a case in central place for my study. It’s a research-based art project. Its seemingly lack of risk-taking reminds me that even I’ve detailed the absorption of unfathomable criticality into manageable risk by capitalistic branded creativity, but it’s not saying that an art that doesn’t risky has no sense of criticality at all. In Commonopoly, a half-mockery half-investigatory project by the group "Big Hope" (1998 - 2006) consists of Miklos Erhardt, Dominic Hislop and Elske Rosenfeld, an oversized paper board adapted from a classic game ‘Monopoly’ is developed for viewers to play. The difference between Monopoly and Commonopoly is that the later made its rule open to public. It invites visitors to come up with their own sets of instructions, usually reflects their local circumstances in which exhibition takes place. It playfully records the local’s ‘perception of economic structures as well as creating alternative, utopian and sometimes absurd playable economic systems’. [12] Along with Tirdad Zolghadr’s Ethnic Marketing, such art projects assimilate back upon existed system, from which they acquire respective artistic strategies, therefore alternately broaden one’s intellectual framework. It seems to me that in this multifaceted impact of different disciplines, a study of the value of creativity needs to inspect dynamically rather than statically. In that sense, my study in the form of word snake hopefully performs the transitory nature of such understanding.- Jump up ↑ Michel Foucault. ‘What is Critique?’ In The Politics of Truth. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. 1997. p. 46.

- Jump up ↑ Jan Verwoert. ‘Vengefulness as muse.’ In Cookie! Berlin: Sternberg Press. 2014. p. 31.

- Jump up ↑ A Crime Against Art. Dir. Hila Peleg. Unitednationsplazastudios, 2007.

- Jump up ↑ Irit Rogoff. ‘What is a Theorist?’ In The State of Art Criticism. Edited by J. Elkins and M. Newman. New York: Routledge. 2008.

- Jump up ↑ Jan Verwoert. ‘Vengefulness as muse.’ In Cookie! Berlin: Sternberg Press. 2014.

- Jump up ↑ Jan Verwoert. “On Seduction Value and Metabolism” in Artists, What Is Your Value series. London: ICA. 25 Feb. 2015. Lecture performance.

- Jump up ↑ Michael Hardt. ‘Immaterial Labor and Artistic Production,’ in Rethinking Marxism 17, no.2 (April 2005): 176

- Jump up ↑ Hilarie M. Sheets. ‘Inspired by an American Icon.’ New York Times 25 Sept. 2012: 13. Print.

- Jump up ↑ See: David Harvey. Spaces of Neoliberalization: towards a theory of uneven geographical development, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005, and, Michel Feher. "The Age of Appreciation: Lectures on the Neoliberal Condition". Lecture series. London: Goldsmiths. Visual Cultures Department. 2013-2015.

- Jump up ↑ How to collect contemporary art––Li Zhenhua’s collection, Shanhai: Studio of Zhang Lehua, 2013.

- Jump up ↑ Giorgio Agamben. ‘The Most Uncanny Thing.’ In The Man Without Content. California: Stanford University Press. 1999.

- Jump up ↑ Big Hope. Project description of Commonopoly. Unknown date.