66 Art Crowd Funding Projects in London 2014

Contents

[hide]The Project

Like crowd funders in their 'About this Project' and 'Risks and Challenges' sections, I believe it is important to be as transparent as possible about the rationale that my body of research was led by. In surveying Projects and interviewing those using crowd funding to get their projects off the ground, I have found that one of the most important aspects of the process is being entirely open about your goals in order to connect to people; therefore I have tried to be extremely honest about every aspect of this research process. Rather than creating a series of explanatory texts or objective, critical essays, I view this research as a series of narratives and conversations with and about the people within these temporal economic networks.

The premise of my project began with data gathering; in sympathy to other projects featured on this Wiki, such as 100 Projects of Crowd Funding In Architecture, or more specific case studies, such as the insights into + Pool and The People's Opera New York City Opera. As the rather dry title (66 Art Crowd Funding Projects in London 2014) suggests, my initial task was to gather data on Crowd Funding within certain self-imposed perimeters defined to lend coherence to the data gathered.

Methodology Rationale

Project Restrictions

The restrictions and stipulations for inclusion in the survey were as follows:

- The Project must have been successfully funded in 2014

- The Project must be based in London

- The Project must describe itself as 'Art' or 'Contemporary Art'

- The Project must have used either Kickstarter or Indigogo

The When, The Where, The Who

As I previously mentioned, the most obvious reason for imposing restrictions on the selection of Projects to survey was to contain the data gathered and make it manageable. As crowd funding is a contemporary economic trend it seemed logical to me to set the time constraints as recent (2014), and make the location boundaries relevant to my own locale. Any projects funded in U.S. Dollars rather than GBP Pound Stirling were not included, as I assumed that the project may not be entirely based in London.

Including only successful projects was much simpler than defining a percentage over which could still be deemed a success despite not having achieved the overall goal. Not including projects which had missed their targets, including ones which had narrowly missed it, was also a reflection of the ways in which many crowd funding websites operate: where unless the project achieves 100% of it's goal within deadline, all of the money raised during the campaign will go to the website.

Deciding to only look at Projects which had used Kickstarter and Indiegogo was in part a way of honing down the data gathered, but also an attempt to reflect the rapidly developing 'mainstream' of crowd funding in the arts. Having specific boundaries for what to and what not to include in my data gathering prior to starting my research allowed for date to emerge that was both specific in it's insights and objectively gathered. The inclusion of projects in this survey does not vouch for the integrity or merit of the project and is not a reflection of my views of what should and shouldn't be funded.

Defining the 'Art' Project'

As my research has discovered, crowd funding is inherently personal, specific and idiosyncratic, often relying on social relations and interaction despite the illusion of distance due to technological interfaces. Therefore it is appropriate that I chose to survey art projects, having recently left art school myself, and having always been creatively persuaded. The merit of research is most often founded on the extent of it's apparent objectivity and thoroughness of investigation from a distance. Yet, all research is instigated by individuals with personal interests, just like all crowd funding projects emerge from an idea a person has had and liked enough to want to make it happen.

It was of course important that the data selection process was objective, so that useful information might be gathered. Therefore, provided that the project was tagged with 'Art' and showed evidence of this being correct, as well as meeting the other restrictions for inclusion (location, currency, success), it was included in the survey.

To be more specific, projects included would be classified 'Fine Art', although this categorising is unappealingly snobbish and a rather unfashionable approach, it was important to be clear about the type of projects to be included in the survey, so that they were more clearly comparable and provided an accurate insight into the sector. This therefore excluded literary projects, design, drama and theatre projects, music projects etc. This also meant excluding film making, (unless of course they were funding artist films), which is increasingly a large sector using crowd funding. Also excluded were design and architecture projects, and commercial art projects such as ‘RED HOT 11 – A LARGE SCALE, COFFEE TABLE ART BOOK! By Thomas Knights’. This project was selected by my 'refined search' as it was based in London and included the word ‘art’ in its title and blurb. However the content: ‘The 100 Sexiest Red Hot Guys in the World’ was not the ‘Fine Art’ that I was looking for. The primary aim of the Projects included had to be the support of artists; artist’s projects; Fine Art Exhibitions and Fine Art Galleries; Institutions and their Projects.

Conversations

As I continued gathering data my spreadsheet too continued to grow, change and self-augment as the project developed, and soon it became clear that there was a sense of disjointedness with the form that my research was taking and the evidence it was producing. The data (and my interest) was concerned with the people initiating these projects, their goals and their networks. However, the formality of the spreadsheet was beginning to smother the individuality of all the projects surveyed, losing sight of what engages people with these projects and makes backers donate. Therefore, in addition to the data gathered, I also conducted a series of short conversations with what began as a random selection of three projects, and ended up as a mini network of connections itself.

Anne Krinsky

Jessika De Wahls

Melissa Sueren

Simon Gwynn

Lucy Sparrow

Jane Moore

The Surveyed Projects

Breakdown of the Surveyed Projects

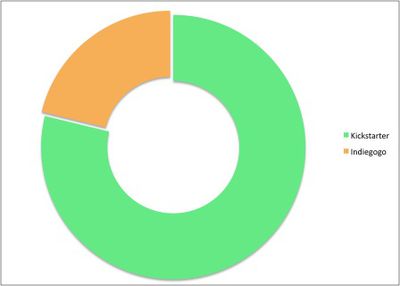

Of the surveyed projects, there was a distinct bias towards Kickstarter as the preferred crowd funding platform. This is most likely due to Indiegogo's increasingly strong association with funding film projects, therefore artists and others wishing to get their art project funded may be more likely to use Kickstarter where they may feel they will get more views from people with relevant interests. Of the surveyed Projects, 52 were funded on Kickstarter and 14 were funded on Indiegogo.

A full break down of the data gathered can be accessed here: File:Crowd Funding Data.xlsx

Chart Showing the breakdown of projects funded on Kickstarter and projects funded on Indiegogo

Bibliography of Surveyed Projects

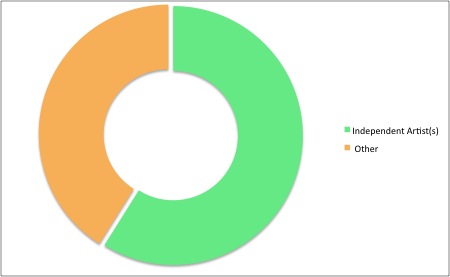

Initiators

There was clear evidence from the data gathered that the majority of the initiators of the Arts Crowd Funding Projects surveyed were professional independent artists, which I felt was unsurprising. A significant minority of projects were set up by students, generally funding their Final Degree shows and looking for extra money to fund the event, exhibition costs and the costs of producing the work (again, a result which I found unsurprising).

Independent Artists Using Crowd Funding

Of the independent artists using crowd funding, their projects varied in theme, financial goal and purpose. As a surveyed group 'Independent Artists Using Crowd Funding' also included independent, informally led groups of artists working together briefly for a shared goal.

Crowd Funding's 'inclusiveness' makes it an appealing option for art projects, as provided a project has a clear aim it is unlikely to be rejected. Unlike other funding bodies, which may require very specific changes to be made and may only be available to artists working with very particular topics, crowd funding platforms have a high acceptance rate and may even accept projects on the same day of submission. In contrast the long applications and slow processing of funding bodies, combined with very particular restraints on a project's theme can prove a hindrance to some projects.

As the artist Lucy Sparrow found, appealing to people's sense of nostalgia and community greatly benefitted her project, whereas Simon Gwynn, despite achieving his target failed to connect to people enough to make his project 'go viral'. However, both projects were accepted by Kickstarter and both were successful, in that they both achieved their goal within the allotted time.

Other organisations and individuals using crowd funding

In addition to independent artists there were also individuals who, although they might have their own artistic practices, their Kickstarter campaign may have been on behalf of an institution or organisation. The Gasworks Studios were using Kickstarter to fund a major development to add new studios to their facilities. Whilst Kristina Clackson Bonnington was working in partnership with University College London Art Museum to fund a collaborative public art project.

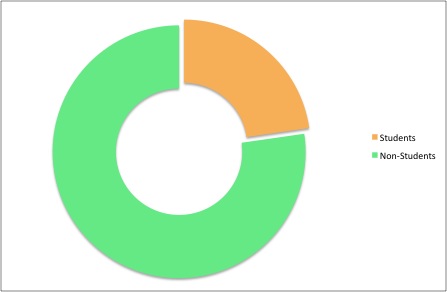

Students Using Crowd Funding

The Students using crowd funding were generally looking for money to support the production costs of their final year exhibitions. Often the money was clearly lined up for a specific aspect of their degree shows, for example Camberwell students were hoping to raise enough money to create a publication to accompany the show.

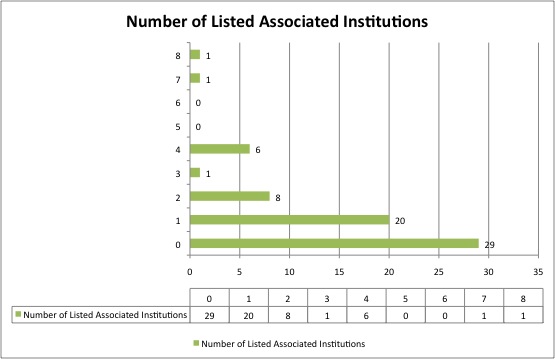

Listed Associated Institutions and Organisations

Many projects sought to boost their visibility and funding potential by gaining other financial support and 'in-kind' support from other institutions and organisations. Of course, many of the projects themselves had been rejected by the Arts Council, or were dependent on reaching their Kickstarter goals in order to gain 'match funding' from the Arts Council. By listing other organisations on their pages that their projects were affiliated with, the initiators sought to expand the exposure of their project, whip up interest around their projects and practices, and sign-post like-minded people to things that they too might be interested in.

Often initiators used institutional logos like seals of approval on their crowd funding pages. Of the surveyed sites the number of institutions listed as associated on project pages varied from 0 to 8. Unsurprisingly, just under half of the projects had no listed support from external institutions and organisations, whilst just under a third listed association with one other institution or organisation. The most any single project has listed on their website was 8. This survey obviously is unable to take into account the number of individuals connected to other institutions and organisations that may themselves have donated and shared amongst their contacts.

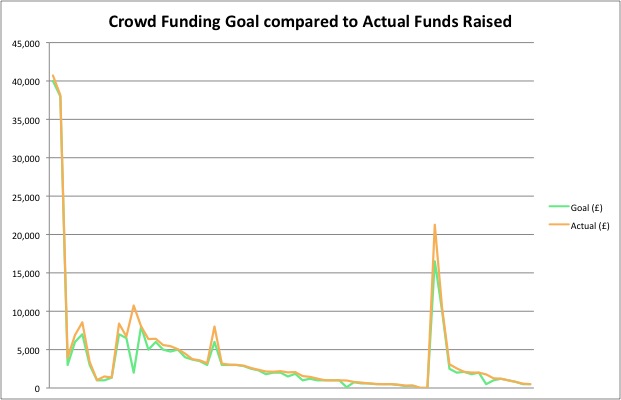

Funding Information

As one of the stipulations for inclusion in the survey was that the project be successfully funded, this section focuses mainly on the difference between the target amount and the actual funds raised, and the break down of the funding. As the three charts below demonstrate, overall there wasn't huge disparity between the target and the actual funds raised.

Funding Chart 1

Funding Chart 1 maps the figures for the Goal of each project in line with the Actual Funds raised for each project (The Goal is indicated by the green line, whilst the orange line indicates the Actual End figure). As both Chart I and Chart 2 indicate, with only few exceptions, the funding target and actual funding outcome were often not hugely different, and generally overlap. I wasn't hugely surprised by this, as I had expected, the cases of people massively exceeding their targets and going viral online were very rare; this is demonstrated most clearly in Chart 3. Even in cases where people had raised large sums, it was often a very close call and it is worth remembering that projects failing to meet their targets will often lose all of the money raised within the time limit. Therefore, it is logical to assume that if a project is struggling at the end to meet target, initiators themselves may 'top up' donations to ensure 'success'.

Funding Chart 2

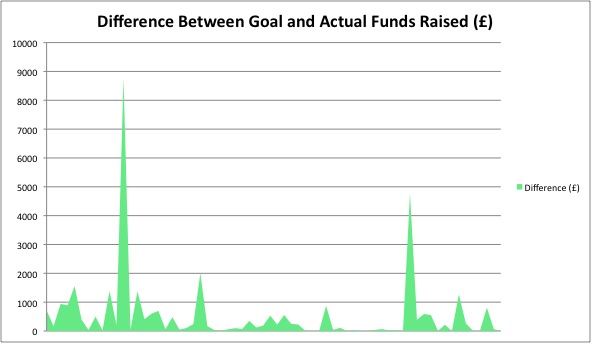

Funding Chart 2 focuses specifically on the differences between actual and goal, whilst leaving the projects in the original order that they were surveyed from Kickstarter and Indiegogo.

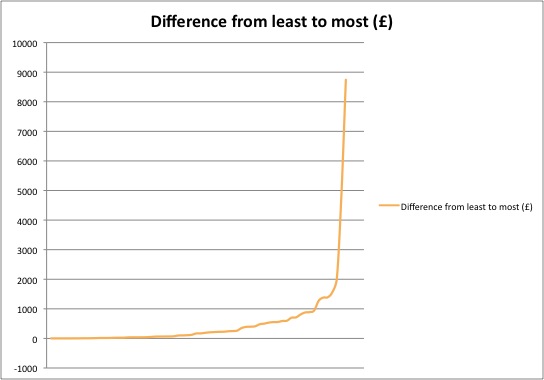

Funding Chart 3

The third Funding chat (Difference from Least to Most) looks at the difference between goal and actual when viewed in numerical order, from £0.00 difference between goal and actual, to the maximum difference where the Actual was £8,744 over the original target. Eleven projects were under £10 over the target, just scraping past their goal needed to gain access to the money they were crowd funding for. 60 out of the 66 projects were under £1000 over their targets, making those greatly exceeding their targets in the minority.

Funding Breakdown

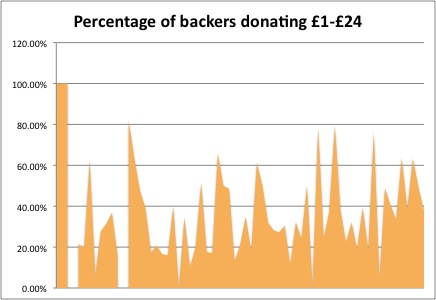

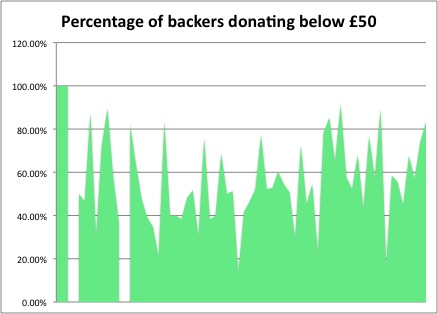

It became clear early on in the research that there was a general pattern of donations being made. In order to make the information gathered easier to process, the categories for the division of donations was simplified, counting roughing in the groupings of: £1 or more; £25 or more; £50 or more; £100 or more; £200 or more; £500 or more; £1000 or more; or £5000 or more. Smaller donations tend to make up the most significant portion of donations, with on average 57.17% of donations being below £50 (see Funding Chart 5), and 37.83% of all donations under £25 (see Funding Chart 4). The crowd funders I spoke to confirmed, and explained that this was often due to people wishing to show their support and giving a token of approval. This is also confirmed by Kickstarter, who give advice to prospective crowd funders to expect an average donation of £17 and advise to have a good selection of rewards, considering what you yourself might expect to receive in return for a donation (Kickstarter, Creator Handbook, 2015).

Funding Chart 4

Funding Chart 5

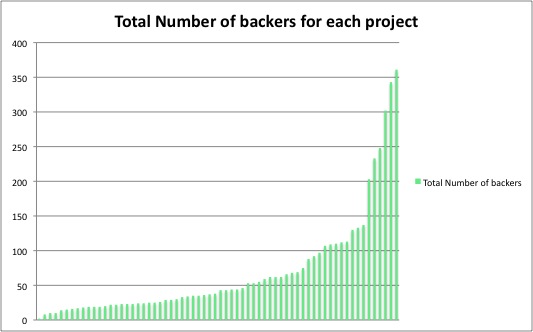

The Backers

The number of backers each project attracted varied greatly from only two people, all the way to 361 people: all prepared to donate money to support artistic projects. The vast majority of projects (60 out of 66) had no more than 150 backers. This was no surprise. As R.I.M. Dunbar discusses in Cognitive Constraints on the Structure and Dynamics of Social Networks, human social groupings have a very distinct size and structure (2008, p.7). In studies across social groups amongst primates the average species social group was found to correlate to the size of the neocortex. This confirmed that the average social group of a human individual was around 150 people.

“Intriguingly, 150 is also the average size of the human social network, where this is definied as the main circle of friends, relations, and acquaintances with whom one keeps in regular contact,..., These individuals seem to be characterised by a level of reciprocity and obligation that would not be accorded to individuals who fall outside this critical circle. These are people whom we feel we are obliged to help out when they need help. In some cases, this sense of obligation arises from direct personal contact, the product of an emotional commitment based on past social interaction.” (Dunbar, 2008, p.9)

This evidence of personal connection between initiator and backer, however tenuous, lends itself to the sense of obligation and exchange inherent in crowd funding. There are of course exceptions from the rule, for example Lucy Sparrow, who's project The Cornershop stole the imagination of people from around the world who funded her despite never having previously met her and being unlikely to ever see the work of art complete. However, the other side to all this, is that a new network of connections and relationships is born as a result of crowd funding. Not only does an artist ensure an engaged and (financially) committed audience, but a new group of fans with whom connections are maintained even if just through mailing lists and social media.

Understanding this relationship between the initiators and backers hugely has shaped my understanding of Crowd Funding as forms of exchange and alternative networks.

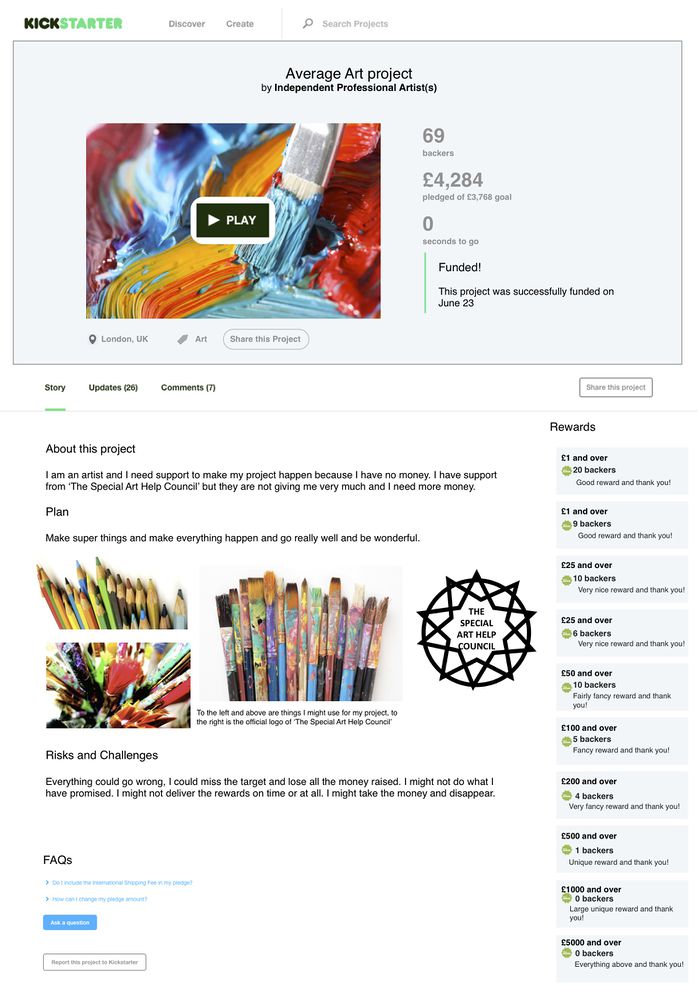

The Average Project

Please see below the imagined Average Art Project as it might look on Kickstarter.

Additional Texts

In response to both the data explored and catalogued on this page, as well as the conversations with initiators I have written texts reflecting on significant aspects of these findings. Please see the links below for these texts:

Exchanges

Networks

Furthermore, responding to my research, I also am delighted to share a short play, suitable for radio broadcast or short performance :

Friends of Friends of Friends of Friends of Friends of Friends of Friends

Bibliography

- Art Cube (2015) Art Cube, Available at: http://www.art-cube.co.uk/ (Accessed: 12 March 2015)

- Boltanski, L. & Chiapello, E. (2007) The New Spirit of Capitalism, London: Verso

- Bourdieu, P. (2005) The Social Structures of the Economy, Cambridge: Polity

- Boyer, B, Hill, D. & Helsinki Design Lab (2013) Brickstarter, Available at: http://www.brickstarter.org/Brickstarter.pdf (Accessed: 15 December 2014)

- Corcoran, S. & Rancière, J. (2010) Dissensus, London: Continuum

- Davidson, J. (2014) ‘We Need To Do Better Than The Ice Bucket Challenge’ TIME, 13 August 2014

- Davidson, R. & Poor, N. (2015) ‘'The barriers facing artists’ use of crowdfunding platforms: Personalities, emotional labour, and going to the well one too many times'’, Available at: http://nms.sagepub.com/content/17/2/289 (Accessed: 21 Feb 2015)

- Dunbar, R.I.M. (2008) ‘Cognitive Constraints on the Structure and Dynamics of Social Networks’, Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, Volume 12, No 1, pp.7-16

- Evans, N. (2005) ‘Size Matters’, International Journal of Cultural Studies, Volume 8(2) pp.131-149

- Feher, M. (2014) The Age of Appreciation: Lectures on the Neoliberal Condition 2013-2015, Lecture 2: Improve Your Credit: What Human Capital Wants [Lecture] 22 January

- Foucault, M. (2008) The Birth of Biopolitics. Lectures at the College de France 1978-1979, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

- Frizzell, N. (2014) ‘Kickended: the enthralling world of crowdfunding flops’ The Guardian, 14 November 2014

- F.S.A. (2014) ‘Crowd Funding: Is Your Investment Protected?’, FSA, Available at: http://www.fsa.gov.uk/consumerinformation/product_news/saving_investments/crowdfunding (Accessed: 17 April 2015)

- Gerber, E.M. and Hui, J. (2013) ‘Crowdfunding: Motivations and deterrents for participation’ ACM Transactions Human-Computer Interactions, Volume 20, 6, Article 34, Available at: http://delivery.acm.org/10.1145/2540000/2530540/a34-gerber.pdf?ip=158.223.171.104&id=2530540&acc=ACTIVE%20SERVICE&key=BF07A2EE685417C5%2E18BBEBD7797679F3%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35&CFID=462319827&CFTOKEN=96471224&__acm__=1418302883_95e46d5f997020c339ba178afd8c61ae (Accessed: 11 December 2014)

- Harvey, D. (2011) The Enigma of Capital: and the crisis of Capitalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Harvey, D. (2013) Warwick University Distinguished Lecture Series – Professor David Harvey – The Contradictions of Capital [Lecture] 25 February

- Kickstarter, (2012) Amanda Palmer: The New RECORD, ART BOOK, and TOUR, Available at: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/amandapalmer/amanda-palmer-the-new-record-art-book-and-tour (Accessed: 5 March 2015)

- Kickstarter (2015) Creator Handbook, Available at: https://www.kickstarter.com/help/handbook (Accessed: 14 March 2015)

- Kickstarter (2014) Kickstarter, Available at: https://www.kickstarter.com/ (Accessed: 29 November 2014)

- Kickstarter (2014) Money for Nothing by Simon Gwynn, Available at: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/simongwynn/money-for-nothing?ref=discovery (Accessed: 11 December 2014)

- Kickstarter (2014) Potato Salad by Zack Danger Brown, Available at: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/324283889/potato-salad (Accessed: 3 March 2015)

- Kickstarter (2014) RED HOT 100 – A LARGE SCALE, COFFEE TABLE ART BOOK, Available at: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/redhotexhibition/red-hot-100-a-large-scale-coffee-table-art-book?ref=discovery (Accessed: 28 December 2014)

- Kickstarter (2014) Staging History: Performance in the Arab world by Delfina Foundation – Kickstarter, Available at: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/238536442/staging-history-performance-art-in-the-arab-world (Accessed: 28 November 2014)

- Krysa, J. (2006) DATA Browser: Curating Immateriality, Brooklyn: Autonomedia

- Larsen, L.B. (2014) Networks, London: The Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press

- Luka, M. E. (2012) ‘Media Production in Flux: Crowd funding to the rescue’, Journal of Mobile Media, Volume 8 No. 2, Nov. 2014. [Online] Available at: http://wi.mobilities.ca/media-production-in-flux-crowdfunding-to-the-rescue/ (Accessed: 4 December 2014)

- Mooshammer, H. & Mortenbock, P. (2008) Networked Cultures: parallel architectures and the politics of space, Rotterdam: NAi Publishers

- Mandiberg, M. (2012) The Social Media Reader, New York and London: New York University Press

- Mauss, M. (1950) The Gift, English Translation re-published 2002, London: Taylor & Francis e-library

- Ostrom, E. (1990) ‘Reflections on the Commons’, Governing the commons: the evolutions of institutions for collective action, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press

- Palmer, A. (2013) '‘Amanda Palmer: The Art of Asking'’, TED, Available at: http://www.ted.com/talks/amanda_palmer_the_art_of_asking?language=en (Accessed: 1 March 2015)

- Roy, A. (2010) Poverty Capital: Microfinance and the making of development, New York: Routledge

- Schofield, H. (2015) '‘French Nepotism Row Over Pompidou Centre Job’', BBC News, 6 March 2015

- Shakespeare, W. The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Campaign,III. Project Gutenberg.

- Verhaeghe, P. (2014) ‘Neoliberalism has brought out the worst in us’, The Guardian, 29 September 2014

- Wallis, L. (2014) ‘Why it pays to complain via Twitter’ BBC News: Business, 21 May 2014

- Where’s George (2015) Where’s George?, Available at: http://www.wheresgeorge.com/ (Accessed: 10 April 2015)

Research by Zara Worth

To continue the conversation on Crowd Funding drop me a message on Facebook!