Difference between revisions of "66 Art Crowd Funding Projects in London 2014"

Zara.worth (Talk | contribs) m |

Zara.worth (Talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 232: | Line 232: | ||

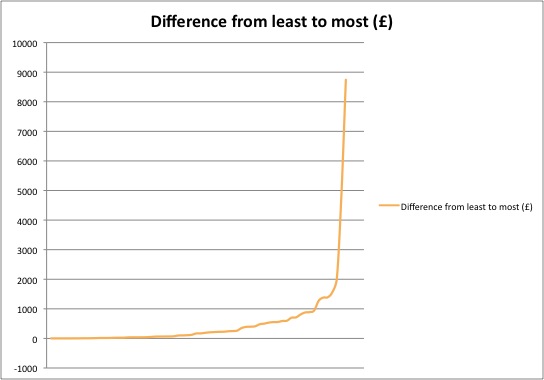

The third Funding chat (Difference from Least to Most) looks at the difference between goal and actual when viewed in numerical order, from no difference between goal and actual, to the maximum difference where the Actual was £8744 over the original target. Eleven projects were under £10 over the target, just scraping past their goal needed to gain access to the money they were crowd funding for. 60 out of the 66 projects were under £1000 over their targets, making those greatly exceeding their targets in the minority. | The third Funding chat (Difference from Least to Most) looks at the difference between goal and actual when viewed in numerical order, from no difference between goal and actual, to the maximum difference where the Actual was £8744 over the original target. Eleven projects were under £10 over the target, just scraping past their goal needed to gain access to the money they were crowd funding for. 60 out of the 66 projects were under £1000 over their targets, making those greatly exceeding their targets in the minority. | ||

[[File:Difference_from_least_to_most.jpg|centre|Difference between Goal and Actual in Numerical Order]] | [[File:Difference_from_least_to_most.jpg|centre|Difference between Goal and Actual in Numerical Order]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==The Backers== | ||

| + | The number of backers each project attracted varied greatly from only two people, all the way to 361 people, all prepared to donate money to support artistic projects. The vast majority of projects (60 out of 66) had no more than 150 backers. This was no surprise. As R.I.M. Dunbar discusses in ''Cognitive Constraints on the Structure and Dynamics of Social Networks'', human social groupings have a very distinct size and structure (2008, p.7). In studies across social groups amongst primates the average species social group was found to correlate to the size of the neocortex. This confirmed that the average social group of a human individual was around 150 people. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote> “Intriguingly, 150 is also the average size of the human social network, where this is definied as the main circle of friends, relations, and acquaintances with whom one keeps in regular contact,..., These individuals seem to be characterised by a level of reciprocity and obligation that would not be accorded to individuals who fall outside this critical circle. These are people whom we feel we are obliged to help out when they need help. In some cases, this sense of obligation arises from direct personal contact, the product of an emotional commitment based on past social interaction.” ''(Dunbar, 2008, p.9)'' </blockquote> | ||

| + | [[File:Total_Number_of_Backers.jpg|centre|Total Number of Backers for each project]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Bibliography== | ||

| + | * Dunbar, R.I.M. (2008) ‘Cognitive Constraints on the Structure and Dynamics of Social Networks’, Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, Volume 12, No 1, pp.7-16 | ||

Revision as of 13:55, 14 March 2015

Contents

[hide]The Project

Just like crowd funders in their 'About this Project' and 'Risks and Challenges' sections, I believe it is important to be as transparent as possible about the rationale that this body of research was led by. In surveying Projects and interviewing the people using crowd funding to get their projects off the ground, I have found that one of the most important aspects of the process is being entirely open about your goals in order to connect to people, therefore I have tried to be extremely honest about every aspect of this research process. Rather than creating a series of explanatory texts, I view this research as a series of narratives and conversations with and about the people within these temporal economic networks.

The premise of this project began with data gathering; in sympathy to other projects featured on this Wiki, such as 100 Projects of Crowd Funding In Architecture, or more specific case studies, such as the insights into + Pool and The People's Opera New York City Opera. As the rather dry title (66 Art Crowd Funding Projects in London 2014) suggests, the initial task was to gather data on Crowd Funding within certain self-imposed perimeters defined to lend coherence to the data gathered.

Methodology Rationale

Project Restrictions

The restrictions and stipulations for inclusion in the survey were as follows:

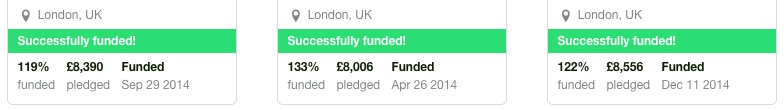

- The Project must have been successfully funded in 2014

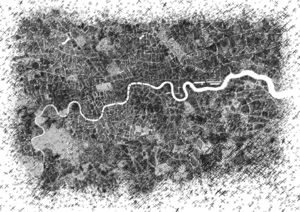

- The Project must be based in London

- The Project must describe itself as 'Art' or 'Contemporary Art'

- The Project must have used either Kickstarter or Indigogo

The When, The Where, The Who

As previously mentioned, the most obvious reason for imposing restrictions on the selection of Projects to survey was to contain the data gathered and make it manageable. As crowd funding is a contemporary economic trend it was logical to set the time constraints as recent: 2014, and make the location boundaries relevant to my own locale. Any projects funded in U.S. Dollars rather than GBP Pound Stirling were not included, as I assumed that the project may not be entirely based in London.

Including only successful projects was much simpler than defining a percentage over which could still be deemed a success despite not having achieved the overall goal. Not including projects which had missed their targets, including ones which had narrowly missed it, was also a reflection of the ways in which many crowd funding websites operate: where unless the project achieves 100% of it's goal within deadline, all of the money raised during the campaign will go to the website.

Deciding to only look at Projects which had used Kickstarter and Indiegogo was in part a way of honing down the data gathered, but also an attempt to reflect the rapidly developing 'mainstream' of crowd funding in the arts. Having specific boundaries for what to and what not to include in my data gathering prior to starting my research allowed for date to emerge that was both specific in it's insights and objectively gathered. The inclusion of projects in this survey does not vouch for the integrity or merit of the project and is not a reflection of my views of what should and shouldn't be funded.

Defining the 'Art' Project'

As my research has discovered, crowd funding is inherently personal and specific, relying on social relations and interaction. Therefore it is appropriate that I chose to survey art projects, having recently left art school myself, and having always been creatively persuaded. It was important that the selection process was objective, so provided that the project was tagged with 'Art' and showed evidence of this being correct, as well as meeting the other restrictions for inclusion, it was included in the survey.

To be more specific, projects included would be classified 'Fine Art', although this categorising is unappealing and unfashionable it was important to be clear about the type of projects to be included in the survey so that they were more accurately comparable and provided an accurate view of the sector. Therefore excluding literary projects, design, drama and theatre projects, music projects etc. This also meant excluding film making, (unless of course they were funding artist films), which is increasingly a large sector using crowd funding; and also excluding projects by individuals who were not arts professionals - anyone who did not identify themselves as primarily involved with the arts, ie. an artist, curator, etc; or identify their motivations explicitly as to support the production of art. Also excluded were design and architecture projects, and commercial art projects such as ‘RED HOT 11 – A LARGE SCALE, COFFEE TABLE ART BOOK! By Thomas Knights’. This project was selected by my refined search as it was based in London and included the word ‘art’ in its title and blurb. However the content: ‘The 100 Sexiest Red Hot Guys in the World’ was not the ‘Fine Art’ that I was looking for. The projects selected must have as their primary aim the support of artists, artist’s projects, Fine Art Exhibitions and Fine Art Galleries, Institutions and their Projects.

The Surveyed Projects

Breakdown of the Surveyed Projects

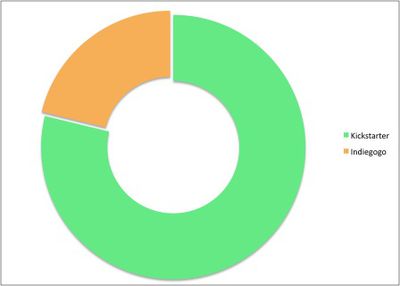

Of the surveyed projects, there was a distinct bias towards Kickstarter being used as a crowd funding website. This is most likely due to Indiegogo's increasingly strong association with funding film projects, therefore artists and others wishing to get their art project funded may be more likely to use Kickstarter where they may feel they will get more views from people with relevant interests. Of the surveyed Projects, 52 were funded on Kickstarter and 14 were funded on Indiegogo.

A full break down of the data gathered can be accessed here: File:Crowd Funding Data.xlsx

Bibliography of Surveyed Projects

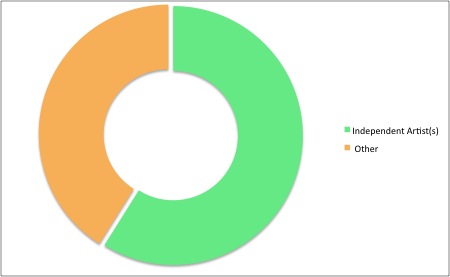

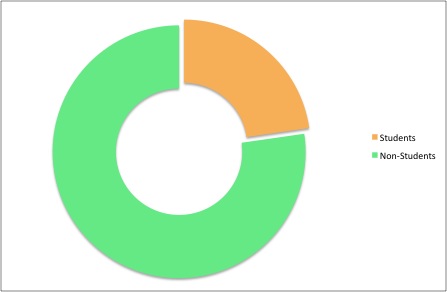

Initiators

There was clear evidence from the data gathered that the majority of the initiators of the Arts Crowd Funding Projects surveyed were professional independent artists. A significant minority of projects were set up by students, generally funding their Final Degree shows and looking for extra money to fund the event, exhibition costs and the costs of producing the work.

Independent Artists Using Crowd Funding

Of the independent artists using crowd funding, their projects varied in theme, financial goal and purpose. The diversity of subject makes crowd funding art projects appealing, but specificity can prove a hindrance to some projects. As the artist Lucy Sparrow found, appealing to people's sense of nostalgia and community greatly benefitted her project, whereas Simon Gwynn, despite achieving his target failed to connect to people enough to make his project 'go viral'. This group also included independent, informally led groups of artists working together briefly for a shared goal.

Other organisations and individuals using crowd funding

In addition to independent artists, there were also individuals, who although they might have their own artistic practices, their Kickstarter campaign may have been on behalf of an institution or organisation. The Gasworks Studios were using Kickstarter to fund a major development to add new studios to their facilities. Whilst Kristina Clackson Bonnington was working in partnership with University College London Art Museum to fund a collaborative public art project.

Students Using Crowd Funding

The Students using crowd funding were generally looking for money to support the production costs of their final year exhibitions. Often the money was clearly lined up for a specific aspect of their degree shows, for example Camberwell students were hoping to raise enough money to create a publication to accompany the show.

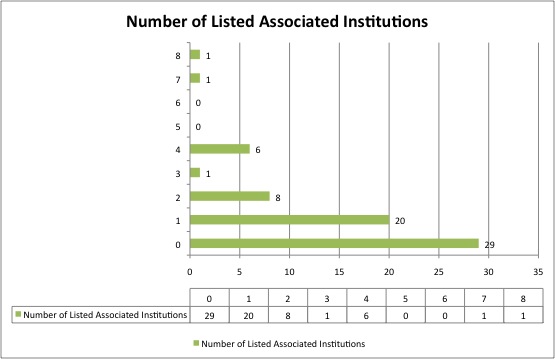

Listed Associated Institutions and Organisations

Many projects sought to boost their visibility and funding potential by gaining other financial support and 'in-kind' support from other institutions and organisations. Of course, many of the projects themselves had been rejected by the Arts Council, or were dependent on reaching their Kickstarter goals in order to gain 'match funding' from the Arts Council. By listing other organisations on their pages that their projects were affiliated with, the initiators sought to expand the exposure of their project, whip up interest around their projects and practices, and sign-post like-minded people to things that they too might be interested in.

Often initiators used institutional logos like seals of approval towards the bottom of their crowd funding pages. Of the surveyed sites the number of institutions listed as associated on project pages varied from 0 to 8. Unsurprisingly, just under half of the projects had no listed support from external institutions and organisations, whilst just under a third listed association with one other institution or organisation. The most any single project has listed on their website was 8. This survey obviously is unable to take into account the number of individuals connected to other institutions and organisations that may themselves have donated and shared amongst their contacts.

Funding Information

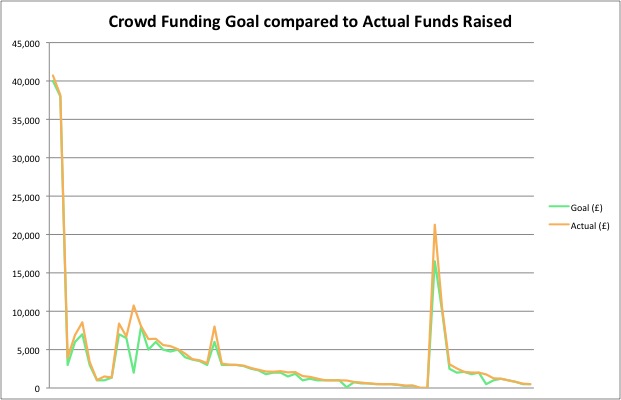

As one of the stipulations for inclusion in the survey was that the project be successfully funded, this section focuses mainly on the difference between the target amount and the actual funds raised, and the break down of the funding. As the three charts below demonstrate, overall there wasn't huge disparity between the target and the actual funds raised.

Funding Chart 1

Funding Chart 1 maps the figures for the Goal of each project in line with the Actual Funds raised for each project (The Goal is indicated by the green line, whilst the orange line indicates the Actual End figure). As the chart indicates, with only few exceptions, the goal funding target and actual funding outcome were often not hugely different, and generally overlap.

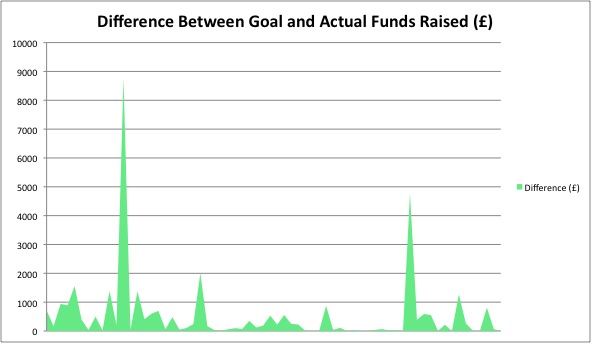

Funding Chart 2

Funding Chart 2 focuses specifically on the differences between actual and goal, whilst leaving the projects in the original order that they were surveyed from Kickstarter and Indiegogo.

Funding Chart 3

The third Funding chat (Difference from Least to Most) looks at the difference between goal and actual when viewed in numerical order, from no difference between goal and actual, to the maximum difference where the Actual was £8744 over the original target. Eleven projects were under £10 over the target, just scraping past their goal needed to gain access to the money they were crowd funding for. 60 out of the 66 projects were under £1000 over their targets, making those greatly exceeding their targets in the minority.

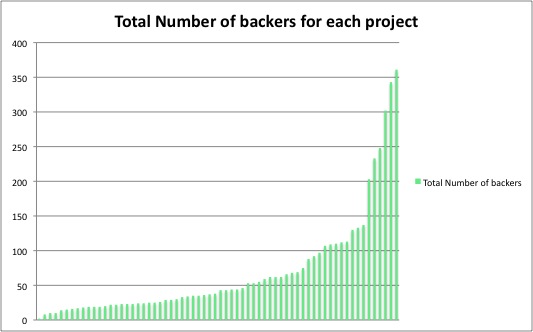

The Backers

The number of backers each project attracted varied greatly from only two people, all the way to 361 people, all prepared to donate money to support artistic projects. The vast majority of projects (60 out of 66) had no more than 150 backers. This was no surprise. As R.I.M. Dunbar discusses in Cognitive Constraints on the Structure and Dynamics of Social Networks, human social groupings have a very distinct size and structure (2008, p.7). In studies across social groups amongst primates the average species social group was found to correlate to the size of the neocortex. This confirmed that the average social group of a human individual was around 150 people.

“Intriguingly, 150 is also the average size of the human social network, where this is definied as the main circle of friends, relations, and acquaintances with whom one keeps in regular contact,..., These individuals seem to be characterised by a level of reciprocity and obligation that would not be accorded to individuals who fall outside this critical circle. These are people whom we feel we are obliged to help out when they need help. In some cases, this sense of obligation arises from direct personal contact, the product of an emotional commitment based on past social interaction.” (Dunbar, 2008, p.9)

Bibliography

- Dunbar, R.I.M. (2008) ‘Cognitive Constraints on the Structure and Dynamics of Social Networks’, Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, Volume 12, No 1, pp.7-16